From Diplomatic Diversification to Power Balancing: Late 1990s to Mid-2000s

The democratization-leading, opposition party that came to power in Korea in 1998 introduced groundbreaking changes into the Korean policy of diplomatic diversification that have continued since the end of the Cold War. With a new government in place, Korea reached beyond mere diversification and sought to play a role in maintaining the balance of power worldwide. The peaceful balance of power necessarily posits the presence of multiple superpowers as well as middle states capable of maintaining or transforming the status quo. This aim at maintaining the current balance of power naturally reflected the increasing stature and influence of Korea on the world stage. However, the attempts by the Kim Daejung and Roh Muhyun administrations to stake out a greater position for Korea amid today’s uni-multipolar world order also contributed to deepening political antagonisms on the domestic front.

(1) Domestic and International Conditions

The “uni-multipolar world” became the key concept capturing the state of world affairs following the Cold War. Table 2-1 shows that the United States still single-handedly leads the world in terms of military strategy and security. Since its victory over the Soviet Union in the armament race, there has yet to emerge a country to challenge the military superiority of the United States. The United States alone spends approximately one half of the total military spending recorded worldwide. The aggregate military spending of the second through tenth most spending states barely manages to occupy two-thirds of the United States’ military spending. On the economic front, however, a multipolar world order is in the making, marked by increasing competition among the United States, China, India, Japan, and the European Union. The EU already surpasses the United States in terms of GDP. The United States is now merely one among multiple superpowers in terms of GDP based on purchasing power.

The current uni-multipolar world order is anticipated to persist for decades to come. The United States is able to spend such an overwhelming amount on its military, notwithstanding its economic decline, thanks to a nationwide consensus on the need to maintain such a spending level. The EU and Japan, on the other hand, lack a comparable public consensus and are unlikely to increase their military spending dramatically, at least for the time being. China and India are still busy at work ensuring the development of their economies, and consequently lean more toward driving economic growth than diverting their investment into military spending. So long as the United States maintains its military spending, which is five times as great as that of the EU, the current distribution of economic power will persist, and so long as China and India remain steadfastly focused on economic rather than military expansion, the uni-multipolar order will remain intact as a self-sustaining mechanism.

Even though the Foreign Exchange Crisis of the late 1990s may have served Korea a major blow, the Korean economy continued to grow after a brief period of structural readjustment. Although there are signs of slowdown, Korea still fares quite well in comparison to other states of similar size and economy. Korea is now one of a dozen or so of the richest countries in the world, and ranks around 20th in terms of economic development (Heston et al., 2006). As Korean politics have matured, the peaceful and democratic transition of power has become an unobjectionable norm. Domestic stability and growth has thus provided the Korean government with the fertile ground it needs for the innovative diplomatic pursuits it seeks out today.

[Table 2-1] Uni-Multipolar World Order

| Rank | GDP (2006) | Military spending (2006) | ||

| State | GDP (PPP; USD) | State | Spending (USD) | |

| 1 | United States | 13.2018 trillion | United States | 528.7 billion |

| 2 | China | 10.48 trillion | United Kingdom | 59.2 billion |

| 3 | India | 4.2474 trillion | France | 53.1 billion |

| 4 | Japan | 4.1312 trillion | China | 49.5 billion |

| 5 | Germany | 2.616 trillion | Japan | 43.7 billion |

| 6 | United Kingdom | 2.1116 trillion | Germany | 37 billion |

| 7 | France | 2.392 trillion | Russia | 34.7 billion |

| 8 | Italy | 1.7954 trillion | Italy | 29.9 billion |

| 9 | Brazil | 1.7084 trillion | Saudi Arabia | 29 billion |

| 10 | Russia | 1.7047 trillion | India | 23.9 billion |

| South Korea (13th) | 1.14 trillion | South Korea (11th) | 21.9 billion | |

Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute 2007; World Bank 2007

Source: Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2008. Korean Public Administration, 1948-2008, Edited by Korea Institute of Public Administration. Pajubookcity: Bobmunsa.

(2) Striking and Maintaining a Balance of Power

The Kim and Roh administrations opted for a strategy of gradual distancing rather than siding actively with the United States in the newly emerging uni-multipolar world order, betraying the growing consciousness of the rise of China and the escalating U.S.-China rivalry in East Asia (Chung, 2001, 779-785). China has been Korea’s largest trading partner since 2004, and is the second biggest source of foreign direct investment in Korea today. Whereas Korea is now witnessing a trade surplus at an unprecedented scale vis-à-vis China, deficits continue to characterize Korea’s trade relations with the West. In other words, China has been a vital and strategic partner for Korea since the dawn of the new millennium. In the meantime, the rivalry between the United States and China is on the rise throughout East Asia, particularly with the United States perceiving the current state of its relationship with China as an old-fashioned rivalry between two superpowers. So long as Washington insists on political reforms and human rights improvements in Beijing, the continuing ideological gap between the two countries will serve to sustain the tension between them (President Bush Jr., 2002, 18, 27-28).

The Kim and Roh administrations sought to position Korea as a “mediator” in the growing U.S.-China rivalry in East Asia and amid the uni-multipolar world order. This policy of insisting on, and maintaining, the balance of power in the region even while seeking greater cooperation with the United States assumed a number of aspects. First, both administrations took an embracing posture toward North Korea. The so-called “Sunshine Policy” significantly differed from the northward policy of the past that sought to encircle and impose changes on North Korea (Cho, 1999). The main objective of the Sunshine Policy was to establish peace and reconciliation on the Korean peninsula. As such, it was more of a policy of managing the North Korean problem than a policy geared toward national reunification (Kim, 2005, 97-104). This North-embracing policy necessarily contradicted the existing traditions of Korean foreign policy that had for decades been singularly centered on Washington’s hegemony.

Second, the new attempts by the Korean government to reinforce the balance of power were even more evident in how it handled the second nuclear crisis in North Korea. The Kim Youngsam administration, facing the first nuclear crisis, delegated the entire matter to Washington after failing to engage Pyongyang in direct dialogue. Washington and Pyongyang, as a result, held high-level official negotiations, with the South Korean government participating in the process only indirectly via U.S. officials (Lee, 1999). Upon the outbreak of the second North Korean nuclear crisis, however, the Korean government sought to ensure room for South Korea’s independence and engaged China in the process in an effort to put the brakes on American dominance over the dialogue. While Korea’s ties to the United States still remain closer than its ties with China, the second nuclear crisis and the subsequent six-party talks distanced Korea from the United States while bringing the country closer to China by comparison.

Third, the hesitation on Seoul’s part with respect to deploying Korean troops to the Second Gulf War also revealed a decisive change in Korea’s policies and attitudes toward Washington. Unlike in the case of the First Gulf War, Washington this time requested that the Korean government contribute a division of Korean combat troops. It was with considerable equivocation and reluctance that Korea eventually decided to deploy its troops, but in the much smaller size of a regiment, and on the condition that they be assigned to combat-free or combat-light areas. President Roh Muhyun, having decided to deploy the troops, asked for Middle Eastern states’ understanding when he held a banquet for Middle Eastern ambassadors at the Blue House on February 17, 2004, explaining that the decision was inspired by the desire “to pay back the great support that Korea received from the international community for its postwar reconstruction and economic development efforts” (The Yonhap Shinmun, February 17, 2004). Thus President Roh attempted to placate both the United States and the Middle East simultaneously.

The new Korean balancing strategy, however, invited serious conflicts not only with Washington, but among the antagonistic ideological and political camps within Korean society as well. The pro-American groups harshly criticized the Korean government’s attempt to position itself as a “mediator,” and strongly opposed both the return of wartime operational control over the Korean forces back to the Korean military and the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Korea; they also lobbied the National Assembly to dispatch troops abroad to aid American war efforts. The opposing social groups welcomed the new role of Korea as an international mediator, voicing their demand for the withdrawal of U.S. troops and the return of wartime operational control over Korean troops, and registering more strongly than ever their objection to the dispatch of Korean troops overseas. The raging conflict between these two opposing groups became an integral feature of daily politics in Korea. The days of limited trans-partisan cooperation over foreign policy were over.

Source: Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2008. Korean Public Administration, 1948-2008, Edited by Korea Institute of Public Administration. Pajubookcity: Bobmunsa.

(3) Changes in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

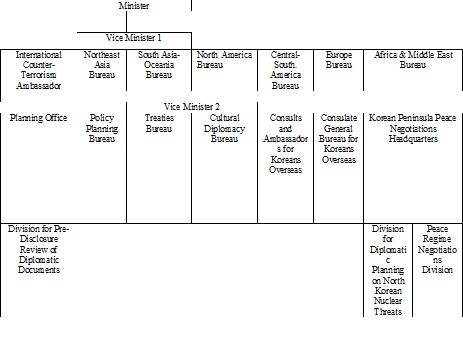

A number of major changes took place in the organization of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs during this period (Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2008). First, the external trade function of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry was transferred to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, thus giving birth to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade in 1998. The Director General of the Trade Negotiations Headquarters was thus given the authority of a Cabinet minister and was also guaranteed a level of autonomy from the command of his superior, the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Second, the organization of the new Ministry closely reflected the mixed state of Korean foreign policy, divided as it was among the three goals of (a) continuing and strengthening the alliance with the United States; (b) ensuring the balance of power; and (c) diversifying the range of diplomatic ties and relations. The Asia-Pacific Bureau was divided into the Northeast Asia Bureau and the South Asia-Oceania Bureau. The former included the Northeast Asia Regional Cooperation, Japan, and China-Mongolia divisions, manifesting the Korean government’s growing consciousness of China’s ascendancy. The Americas Bureau, on the other hand, was broken up into the North America and Central-South America bureaus. The elevation of the North America Division into a bureau on its own right reflected the persistent strategic importance of the United States in Korean foreign policy. The North America Bureau included North America Division 1, which exclusively handled U.S.-Korea relations; the Korea-U.S. Security Cooperation Division; and North America Division 2, which handled relations with the U.S. Congress and Canada. Third, the units in charge of public relations, including those divisions responsible for maintaining and disclosing important diplomatic documents, also grew in status and role, reflecting the progress of democracy in Korean society at large. Diplomacy had long been an area of secrecy and backroom dealing, even though open diplomacy had become the norm elsewhere in the democratic world. With the advancement of democracy rose the public’s right to knowledge and information. Accordingly, the Division for the Pre-Disclosure Review of Diplomatic Documents came into being. Fourth, the new Ministry came to include the Special Countermeasures Headquarters, responsible for addressing urgent issues not assigned to any specific bureaus or offices, such as peace negotiations with North Korea, and energy and climate change issues.

As shown in Table 2-2, the new Ministry arranged its diplomatic establishments overseas according to the importance of the regions or areas in which they were to be located. First, the presence of resident embassies reflected the importance of the hosting countries in international politics. There are therefore more Korean resident embassies found in North America, Asia, and Europe, than in Africa. Second, consulates general were maintained and opened according to the size of the local Korean population. These establishments are thus heavily concentrated in Asia and North America.

[Table 2-2] Korea’s Diplomatic Establishments Abroad (October 2007)

| Region | Resident embassies | Consulates general | Representative offices | Total |

| Asia-Pacific | 24 (14) | 18 (2) | 0 (0) | 42 (16) |

| Americas | 19 (4) | 13 (0) | 1 (1) | 33 (5) |

| Europe | 33 (12) | 6 (1) | 2 (2) | 41 (15) |

| Middle East | 17 (5) | 2 (0) | 0 (1) | 19 (6) |

| Africa | 11 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (8) |

| Total | 104 (43) | 39 (3) | 3 (4) | 146 (50) |

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2008. Figures in parentheses indicate the number of North Korean diplomatic establishments in the respective categories and regions.

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2008

[Figure 2-7] Organization of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade

(Announced on February 20, 2008)

Source: Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2008. Korean Public Administration, 1948-2008, Edited by Korea Institute of Public Administration. Pajubookcity: Bobmunsa.