Second Republic

(1) Organizational Changes

The Second Republic retained much of the police organization of the First Republic, except for reducing the scope of the Special Investigation Division’s tasks from policing politics, culture, and foreigner affairs to policing foreigner affairs only, and also from the investigation of special criminals and general surveillance to the investigation of special criminals only. The scope of police surveillance, however, was broadened to include counter-communism activities, thus reinforcing police control over social stability and order.

[Figure 2-2] Organizational Changes in the Police in the Second Republic

| First Republic | Second Republic |

| Apr. 20, 1959 | Jun. 1, 1960 |

| General Management Dept. | General Management Dept. |

| Security Dept. | Security Dept. |

| Security Guard Dept. | Security Guard Dept. |

| Special Intelligence Dept. | Intelligence Dept. |

| Investigation Instruction Dept. | Investigation Instruction Dept. |

| Communication Dept. | Communication Dept. |

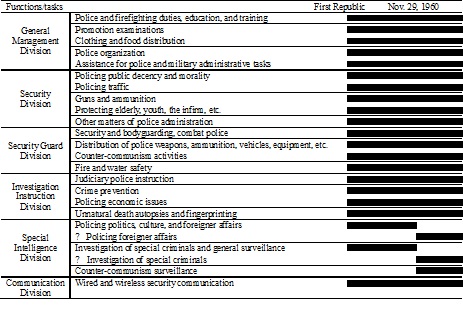

[Table 2-5] Changes in Police Functions and Tasks in the Second Republic

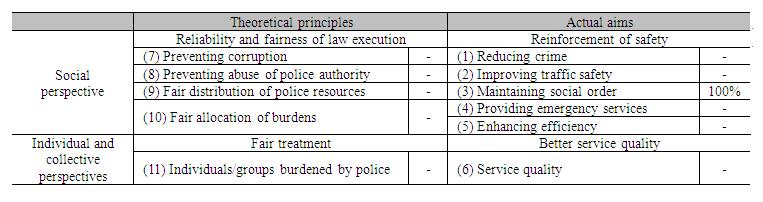

[Table 2-6] Police Principles and Aims in the Second Republic

Source: Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2008. Korean Public Administration, 1948-2008, Edited by Korea Institute of Public Administration. Pajubookcity: Bobmunsa.

Third Republic

(1) Organizational Changes

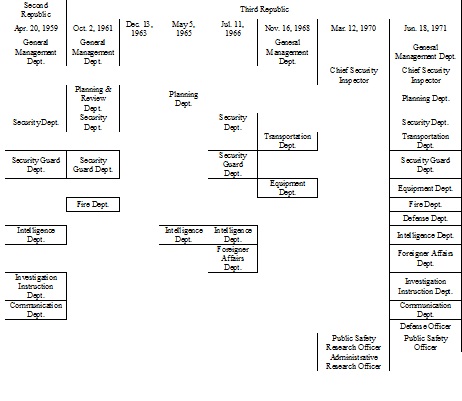

The Third Republic carried out seven division-level reforms within the police organization, which are summarized in Figure 2-3. First, the Planning and Review Division and the Public Safety Monitoring Officer were detached from the General Management Division on October 2, 1961, and March 12, 1970, under Cabinet Decree 166 and Presidential Decree 4722, respectively. The Foreigner Affairs Division was also detached from the Intelligence Division on July 11, 1966, under Presidential Decree 2602, reflecting an overall trend toward greater specialization. Second, combat police units were installed in Seoul and in each province to facilitate inland military operations. This also led to the creation of the Operations Subdivision in the Security Guard Division on September 1, 1967; “five-minute-mobilization-and-strike” teams in all police stations nationwide on February 26, 1968, under Presidential Order 19 (“Instructions in Preparation for Full Warfare”); and the Defense Division on November 16, 1968, under Presidential Decree 3639, to oversee matters of the Homeland Reserve Forces. The position of the Administrative Research Officer was also newly created on March 12, 1970, under Presidential Decree 4722, and charged with conducting research on the police organization and personnel, as well as the traffic police system. The position, however, was abolished the following year. The position of the Defense Officer was created on June 18, 1971, under Presidential Decree 5675, to oversee matters of the Civil Defense Guard, the Homeland Reserve Forces, counter-communism intelligence, the policing of foreigner affairs, and security guard tasks. These new features upheld the trend of militarization of the police organization.

[Figure 2-3] Organizational Changes in the Police in the Third Republic

(2) Functional Changes

The Third Republic[1] introduced a total of 39 new tasks into the police organization. Forty-four percent of these tasks pertained to maintaining social order; 23 percent, to enhancing efficiency; 10 percent, to improving traffic safety; 8 percent, to reducing crime; and 5 percent to providing emergency rescue services, preventing corruption, and preventing the abuse of police authority each.

The proportion of tasks for maintaining social order remained high as the Third Republic continued to emphasize public preparedness in the case of against possible invasions by North Korea. Accordingly, the Third Republic created the Combat Police Force in 1966, and after an attempted attack on the Blue House by communist guerillas in 1968 inserted “five-minute-mobilization-and-strike” teams in each police station across the nation. Moreover, the Third Republic set up Homeland Reserve Forces in 1969, and began to organize the Taegeuk Exercises (now known as the Ulchi Focus Lens Exercises) in July 1968, thus boosting police involvement in military operations.

The amendment of the Homeland Reserve Forces Act (HRFA) on May 29, 1968 as Law 2017 gave the police operating authority over the Homeland Reserve Forces (i.e., their mobilization, education, and training as well as equipment maintenance), which significantly interfered with essential policing duties. Moreover a new counter-communism and anti-espionage organization was created comprised of 37 squadrons (almost 4,100 of police officers). As the average age of this group began to exceed 30, however, the Korean government enacted the Combat Police Force Act (CPFA) on December 31, 1970 as Law 2248 with the support from the Ministry of National Defense (MND) and other related ministries and departments. The Enforcement Ordinance for the CPFA (Presidential Decree 5582) came into being on March 30, 1971, which required the police to recruit 1,552 agents for the newly created CPF and replace the 37 squadrons of the CPF with members of the general police force (MHA PSHQ, 1985, 273-274). Though the Third Republic ridded the police organization of its duties to provide assistance for police and combat operations as well as military administrative tasks, it imposed a whole host of new duties and responsibilities in their place in the form of operation and training of the Homeland Reserve Forces (as stipulated under Presidential Decree 3731 of January 15, 1969). The police organization’s role in counter-communism and anti-espionage operations also grew, with the police now required to gather an even wider range of counter-communism information and investigate a broader scope of anti-national crimes. All these new tasks kept the police from reducing crime and performing other essential functions in society.

The Police Officers Act (POA) enacted on January 1, 1969 as Law 2077[2] aimed for a large part at enhancing the efficiency of the police with tasks towards this end taking up 24 percent of the new police organization. The POA applied a differentiated ranking system to police officers that acknowledged the different requirements and skills demanded of them; implemented a military-style division system to the police organization that encouraged the specialization of skills and tasks; and introduced remuneration and pension systems that better reflected the police organization’s particular tasks and circumstances, as well as other measures that encouraged the movement of skilled officers up the organizational ladder.

Third, emergency rescue services in cases of disasters involving fire and water were also introduced into the police organization. The reform of the MHA organization on October 2, 1961, led to the creation of the Fire Division in the Public Safety Bureau. The Fire Division was subdivided into the disaster prevention and fire extinction divisions, which together handled disaster prevention, fire safety, emergency water rescue, and other related activities.

Fourth, inspection and auditing tasks were also added to the police organization as part of efforts to prevent corruption and the abuse of police authority. Having enacted the Police Ethics Charter on July 12, 1966, the government reorganized the MHA again on March 12 to create the position of the Public Safety Auditor, and established the Rules of Police Inspection and Auditing on January 21, 1971, under MHA Order 276, concretizing the terms of and actions for corruption prevention.

It should be noted that the MHA organizational reform of March 12, 1970, under Presidential Decree 4722, also led to the re-phrasing of police duty from “protecting the elderly and the infirm” to “protecting and instructing the elderly, the infirm, and youth.” This was a meaningful change since it was the first time in Korea’s legislative history that “youth” were considered state-protected subjects. The Public Safety Bureau and the municipal and provincial police bureaus nationwide came to include youth crime prevention units or divisions by January 1963. Prior to these units, police duties and responsibilities regarding youth pertained to the search for and custody of missing or wayward youth and policing homeless and vagabond teens. The police, until this time, had applied the same crime prevention and handling methods to youth that they had used for adults. In other words, no special efforts were made to take into account the age-specific conditions of crimes (MHA PSHQ, 1985, 98). The absence of such considerations, however, may have reflected the more fundamental belief that police services should be provided without discrimination, and the awareness of the crucial role of police in crime prevention.

[Table 2-6] Police Principles and Aims in the Third Republic

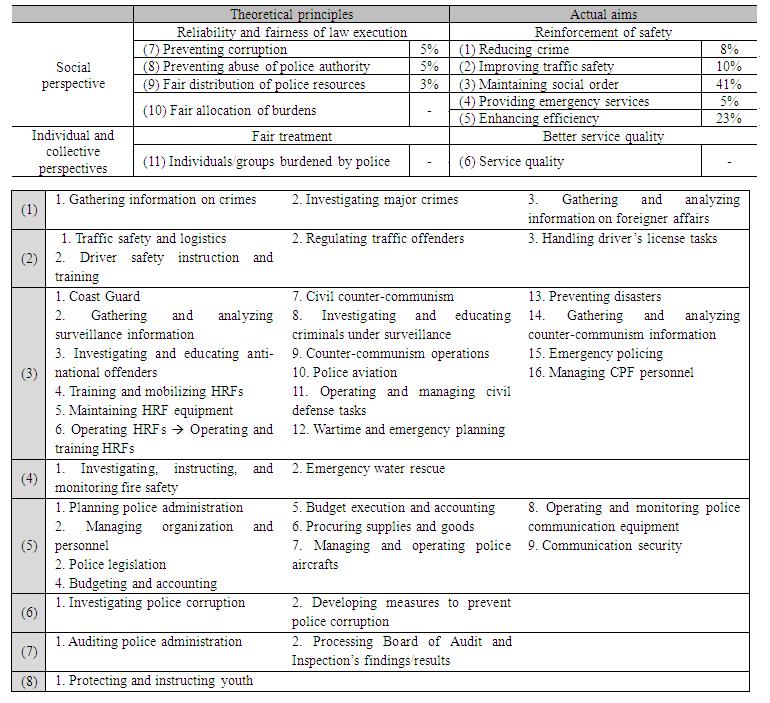

[Table 2-8] Changes in Police Functions and Tasks in the Third Republic

Source: Korea International Cooperation Agency. 2004. Study on Development Aid and Cooperation for South Korea: Size, Scope and Exemplary Effects. Seoul.

Fourth Republic

(1) Organizational Changes

Mun Segwang’s attempt to assassinate President Park Chunghee on August 15, 1974, reawakened the Korean government to the vital importance of security. Thus the police organization went through another transformation. On December 24, 1974, the amended National Government Organization Act (NGOA) was enacted, elevating the Public Safety Bureau at the MHA to the state of the Public Safety Headquarters, and raising the position of the head of the new organization to Assistant Vice Minister. The positions of the public safety and civil defense officers were abolished, giving way instead to Public Safety Departments 1, 2, and 3. The position of the Public Safety Auditor was also replaced with the Personnel Training Division.

The reorganization of the Public Safety Headquarters (PSHQ) continued with the creation of the Civil Defense Headquarters and the replacement of the fire and defense divisions in Department 2 with the Operation Division on August 26, 1975, under Presidential Decree 7760. The Information Division in Department 3 was divided into Information Divisions 1 and 2 on April 15, 1976, under Presidential Decree 8078.

Presidential Decree 8533 of April 9, 1979, installed the Coast Guard Division in Department 2 in response to the rapidly rising demand for protection and patrolling along fishing routes and emergency rescue services from marine accidents. On August 9, 1978, under Presidential Decree 9124, the Coast Guard Division was reorganized into the Maritime Security Division, with the monitoring and prevention of sea pollution added to its range of tasks (MGA, 1981, 477). Security and public safety were the guiding ideals of organizational reforms during this period.

[Figure 2-4] Changes in the Police Organization in the Fourth Republic

(2) Functional Changes

There were 29 new tasks introduced in the police organization during the Fourth Republic. Forty-eight percent of these new tasks were concerned with maintaining social order; 24 percent with enhancing efficiency; 7 percent with reducing crime or providing emergency rescue services; and 5 percent with preventing corruption, preventing the abuse of police authority, and ensuring the fair allocation of burdens each.

The number and scale of demonstrations were on rise throughout the Fourth Republic, as President Park dissolved the National Assembly, declared martial law, and forcefully amended the Constitution—albeit via a nominal public vote—to perpetuate and solidify his rule (Oh, 1997). Police work during this period focused on ensuring external and internal security by deterring possible attacks from North Korea from without, and rounding up communist sympathizers from within. This explains the relatively high proportion (48 percent) of new tasks that focused on maintaining social order. The Public Safety Bureau was elevated and expanded into the Public Safety Headquarters (PSHQ) on December 13, 1972, with the Intelligence Division added to its Department 3. The Intelligence Division gathered a wide range of information on possible and actual espionage going on in Korean politics and society in general, and also investigated suspected or actual crimes anti-national and/or communist in nature. The organizational reform ordered under Presidential Decree 8078 in April 1976 subdivided the Intelligence Division into Intelligence Divisions 1 and 2, charging the former with gathering intelligence in general and the latter with gathering intelligence specifically for counter-communism purposes. The Coast Guard Division came into being in 1977, with the coastal security tasks of the Security Guard Division detached and given their own organization. In 1978, the MHA further divided the Security Guard Division into the maritime security and operations divisions, thereby making it a police task to operate the Maritime Pollution Dispute Arbitration Committee (MPDAC) and the Maritime Pollution Prevention Advisory Board (MPPAB). The tasks of civil defense and fire safety, originally handled by the police, were transferred to the Civil Defense Headquarters newly created in the MHA in 1974. The expansion of the Public Safety Bureau into the PSHQ naturally made enhancing efficiency the second most important (24 percent) police task.

In the meantime, the private police system was introduced to make better use of available, semi-professional police officers. The dramatic increase in the number of demonstrations protesting the passage of the Yushin Constitution on October 17, 1972, compelled the police to expand their numbers to quell the protests, increasing the number of men available for mobilization from nine squadrons (1,004 persons) in 1974 to 21 squadrons (3,994 persons) in 1979 (MHA PSHQ, 1985, 995). Not even this dramatic increase in police recruitment could satisfy the demand, however, so the police began to hire private police officers for the purposes of guarding facilities and transportation, and for controlling access to key facilities. The new private police system represented a new approach to the management of public safety. The number of private police thus hired reached 12,587 in 1979 (MHA PSHQ, 1985, 1000).

[Table 2-9] Police Principles and Aims in the Fourth Republic

[Table 2-10] Changes in Police Functions and Tasks in the Fourth Republic

Source: Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2008. Korean Public Administration, 1948-2008, Edited by Korea Institute of Public Administration. Pajubookcity: Bobmunsa.