all

U.S. Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK)

U.S. Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK)

I. Introduction

The national crises and tumultuous events that occurred in Korea in succession, i.e. Japan’s invasion and colonization, the country’s liberation from Japan after the latter’s World War II defeat, and the outbreak of the Korean War, along with the idiosyncrasies of leaders and other structural factors at home and abroad, all led to fragmentary institutional changes in the country and added unique elements to Korea’s history and culture. Such events occasioned the introduction and adaptation of foreign institutions in the Korean environment, and exerted far-reaching influences, both positive and negative, on the development of public administration here.

Of the diverse events and factors that shaped modern public administration in Korea, the most notable is the period of the U.S. Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK), which lasted from the moment of national liberation on August 15, 1945, to the establishment of the First Republic of Korea on August 15, 1948. As Koreans, who were deprived and brutalized for years under the Japanese colonial regime, struggled to seize their national autonomy and sovereignty after liberation, the U.S. Army set about instituting a de-facto government in the country to maintain some order. The USAMGIK governed Korea to the south of the 38th Parallel in the immediate aftermath of national liberation and served as a central actor in the birth of the modern nation-state in South Korea. U.S. policies and ideologies came to realign social and political groups in Korea and structuralize the divide among them.

Accordingly, the period of the USAMGIK, along with the Joseon era and the Japanese colonial period, forms one of three major factors behind the birth and evolution of public administration in Korea. It is also remembered as the period that established the archetypes of Korean political and administrative institutions and formed the country’s socioeconomic structure. It is not an overstatement to say that the three years of the USAMGIK paved the way for the next six decades of administration in Korea. Simply put, the history and structure of administration in Korea cannot be understood without discussing the USAMGIK first.

The purpose here is to delineate the formation and impact of the political and administrative institutions in Korea under USAMGIK through an institutionalist lens. First, this study surveys the established literature and debates on the major institutional changes that took place during the USAMGIK period and the crisis theories that can be applied to such shifts. Second, we analyze the dynamics of national crises and the actors involved as major variables in the institutional changes led by the USAMGIK. Based on the two foregoing sections, we will then examine the administrative practices and policies that constitute the substance of institutional changes that took place under the USAMGIK. Finally, we summarize the impact of the USAMGIK period on public administration in Korea in past, present and future terms.

Taking a historical institutionalist stance, this study analyzes the administrative systems and policies of the USAMGIK within the context of then domestic and international conditions. This study uses literature review as it main methodology, drawing upon a wide range of newspaper articles, academic journal articles, and other types of existing literature on the USAMGIK to inform its viewpoints.

II. Theoretical Background

1. Types of and Logic Informing Institutional Changes

Historical institutionalism has its origin in the works of the so-called neo-Weberian state theorists of the 1980s who were mainly interested in how institutional changes take place against the backdrop of state-society dynamics and policy networks (Ikenberry, 1986; Skocpol, 1959; Jessop, 1991). These middle-range theories were adapted in Korea in the early 1990s to explain the dynamics between the state and social classes, and the relative autonomy and capability the state exercised in those dynamics. Institutional formation and changes were thus relatively neglected in the discourse (Kim, 1992; Kang et al., 1991). By the late 1990s, however, historical institutionalism had emerged in Korean academic circles as an alternative framework for explaining the mechanism of institutional change and maintenance (Ha, 2003; Jeong, 1999; Kim, 2002; Ha, 2001).

Historical institutionalism divides institutional changes into three types. Grouped in the first type are institutions that change gradually, incrementally, and continually; second are those that experience more radical changes that punctuate the given equilibrium; and third are those with changes that first punctuate a given system, but later lead to gradual and incremental changes in each of the broken parts (North, 1990; Krasner, 1984; Skowronek, 1982).[1]

Of these, it was North’s theory of gradual and incremental (i.e., path-dependent) changes that drew the most attention. The theory of path-dependent changes posits institutional changes as the results of a slow and continuous process, and emphasizes institutional continuity. Path-dependency is a concept that is used to explain what determines the different outcomes of institutional evolution over time. It holds that past decisions necessarily form the background for today’s decision making, while today’s decisions decide the ways in which future decisions will be made and changed (Min, 2002, 79). Official norms or institutions at T2 are results of the formal and informal interactions and restraints at T1, and will lead to a new institutional equilibrium at T3 (Krasner, 1988, 66-72; Bang and Kim, 2003). How actors with different interests interact with one another in different contexts also leads to different institutional forms and outcomes. Pressures operating on institutional formation can be both internal and external (Lee, 1993, 240-241; Kim, 2007, 16). North’s theory of path-dependent changes, however, fails to explain non-continuous institutional changes.

In reality, we see much more radical institutional changes leading to the emergence of new and unexpected institutions than North’s theory would have us believe. Internal or external crises can raise the resistance of existing institutions. Krasner posits that once the level of pressure operating on an institution reaches the breaking point, the existing institution collapses and a completely new institution comes to replace it abruptly. Institutional continuity is hardly on display in these situations that are known as punctuated equilibriums (1983, 242-243). Though Krasner emphasized that institutional changes come about as a result of punctuation in the existing equilibrium, he was also aware that internal resistance and the efforts by state organizations to maintain the status quo made it more difficult than imagined to realize these changes. States necessarily make efforts to ensure that changes and reforms are contained in the existing institutional structure.

North did acknowledge the fact of radical institutional changes in reality (1990, 90-91), but continued to emphasize that even seemingly non-continuous and abrupt institutional changes come about as a result of the existing path. He held that what appears to be punctuations in the equilibrium in the short run are more properly part of incremental changes occurring in the long run. North pointed out that institutional paths progress not in a linear manner, but more on the basis of dialectics (Bang and Kim, 2003), and listed wars, revolutions, conquests, natural disasters, and other such factors as causes of short-term, non-continuous changes (North, 1990, 89).

Source: Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2008. Korean Public Administration, 1948-2008, Edited by Korea Institute of Public Administration. Pajubookcity: Bobmunsa.

Crises that prompt radical institutional change may be defined as “sporadic and sudden events that challenge the state’s capacity for maintaining control and cause a change to the limits on the repression mechanisms within legal boundaries” (Skowronek, 1982). These crises may have their origins internally or externally. Internal crises are prompted by dynamic changes within society at large; while external crises originate from risks inherent in the international system and lead to social resistance on the domestic front (Skocpol, 1979, 31; Krasner, 1984, 234). In times of crises, institutions try to adjust and correct the increasing discrepancy in the changing environment not by maintaining the status quo, but by adopting new game rules. Crises thus give birth to new organizations, and exert their own force so that the manners of extracting social resources, the sociology of the individual, and the basic characteristics of civil society change profoundly. As the situation reaches a new equilibrium over time, new institutions become established. Crises that challenge existing institutions and the policy measures taken in response to such challenges lead to the institutional transformation, with the political and policy choices made by the political elite deciding the success or failure of the changing institutions. The institutional choices made by advanced states at certain points in time also affect the range of choices available for developing states at a later time (Krasner, 1984, 240-245). Various theories exist to explain how crises lead to radical institutional changes.

Crisis theories can take a liberal or Marxian bent depending on which ideological perspective the theorist adopts (Kim, 1992). Examples of Marxian crisis theories include the capitalism crisis theory, the dependence theory, and the world system crisis theory (Gordon, 1987; Anglietta, 1979; Wallerstein, 1984; Chilcote, 1981). Such Marxian theories tend to emphasize macroscopic class struggles over and above the roles of state organizations and institutions, and are thus well suited to my purposes here. Liberal theories, on the other hand, find the causes of crises in the intersectoral imbalances or frictions that occur with existing institutions during the modernization process, and divide crises into the political, the economic, the cultural, and the psychological. Liberal theorists thus find the causes of political crises in political institutions, organizations, leadership, elite dynamics, and government failures (Huntington, 1968; Tilly, 1975; Linz, 1978; O’Connor, 1973; Skocpol, 1979). Those leaning more toward psychological explanations hold that individual frustrations and resistance lead to crises (Lerner, 1963, 330; Davis, 1962; Gurr, 1970). Economic crises are explained through the long-wave theory or are attributed to excessive government spending.

Crisis theories can be further divided according to whether they locate the cause of the crisis internally or externally. In her study on crises and revolutions in France, Russia, China and elsewhere, Skocpol (1979) argued that external factors exerted greater influence on the crises in these countries than internal ones, pointing to the excessive rivalry among foreign armies as the reason for the exacerbated domestic socioeconomic conditions that led to the crises in these states. Examples of foreign pressure or support leading to domestic political and economic crises can be found in numerous historical events, including the rise and fall of the Somoza Government and the Korean War that culminated in the partitioning of the Korean peninsula. In contrast, some theorists hold that internal factors like the lack of cohesiveness and common ideology in the elite group are decisive factors leading to crises. They assert that this internal division, in the absence of external risks, drives ordinary situations to the brink of emergency (Kim, 1992, 58).

Crises are also explained according to their functional aspects, and are generally divided into five types: identity crisis, legitimacy crisis, participation crisis, distribution crisis, and penetration crisis (Binder, 1971, 52-66). Table 4-1 offers a detailed description of each crisis type.

[Table 2-1]

| Type | Definition |

| Identity crisis | A crisis that is generated by the contradiction or conflict between modernity and tradition as a society makes a transition from a pre-modern phase into a modern one. |

| Legitimacy crisis | A crisis that questions the traditional views of political obedience and obligation, which arises in the midst of a societal shift from a traditional, hereditary, absolute model of state authority to a more modern, legal, and rational model. Closely intertwined with identity crises. |

| Participation crisis | A crisis that arises when the people’s demand for political participation expands but the state fails to provide modern political systems capable of accommodating that demand. |

| Distribution crisis | A crisis that is ignited when the people come to believe the government responsible for guaranteeing a minimum standard of living, and begin to demand tangible benefits and services from the government in this regard. |

| Penetration crisis | A crisis that arises in a state in the process of modern political system development, as individuals and social groups seek greater freedom from government control while the government attempts to penetrate deeper into civil society. |

Source: Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2008. Korean Public Administration, 1948-2008, Edited by Korea Institute of Public Administration. Pajubookcity: Bobmunsa.

3. Analysis Framework

There is indeed a wide range of theories that explain the origins and types of institutional changes. Modernization in Korea began on a full scale in the decades between the last years of the Joseon Dynasty and the end of the USAMGIK. These decades are characterized by national crises of an unprecedented scale that definitely punctuated the institutional equilibrium. It was during these decades that the pre-modern, traditional system of politics and administration gave way to new national and social systems. These decades also decided the path of public administration in Korea for the next six decades.

The USAMGIK period is analyzed here not in the context of the overall history of public administration in Korea, but as a new institutional development that ensued at the end of the Japanese occupation period. In other words, the USAMGIK occasioned the transformation of institutions that had been established in the Joseon era and in the Japanese occupation period. This study therefore examines how the new institutions founded under the USAMGIK affected the government institutions and organizations later established in the First Republic. In particular, this study seeks to shine a light on how the interactions and dynamics within the USAMGIK, which faced a nation in crisis, gave birth to new institutions, and how these institutions affected public administration in Korea subsequently.

This study adopts the perspectives of both the path-dependent theory of incremental institutional changes and the radical theory of institutional changes. The latter theory emphasizes the roles of crises and interactions among the involved actors in the founding of new institutions. Accordingly, this study defines the national crises faced by the USAMGIK and how such crises determined the resulting institutional changes, and then analyzes whether the institutional changes under the USAMGIK indeed amounted to a radical departure from those of the Japanese occupation period or remained path-dependent.

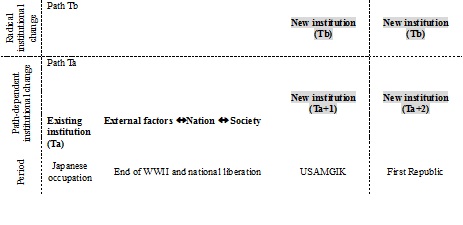

Facing a crisis, existing institutions give way to new institutions and organizations that are shaped by the choices and interactions of the diverse actors involved. New institutions that significantly differ from earlier ones (along Path Tb) mark the given national crisis as the decisive factor of radical institutional change. New institutions that remain on the path or within the boundaries of earlier ones (along Path Ta) indicate that the context and influence of existing institutions form more important variables in the given instance of institutional change than the national crisis. Figure 4-1 illustrates this assumption.

[Figure 3-1] Frame of Analysis

Source: Korea International Cooperation Agency. 2004. Study on Development Aid and Cooperation for South Korea: Size, Scope and Exemplary Effects. Seoul.

III. Dynamics between National Crises and USAMGIK Actors

1. Changing Internal and External Conditions and National Crisis

(1) Deepening Ideological Crisis amid the Cold War and the Rising Threats of National Separation

The USAMGIK was established in an atmosphere characterized by escalating tension between the United States and the Soviet Union, a tension which extended into the Korean peninsula and later became known as the Cold War. Having achieved victory in World War II in alliance with the United States and Great Britain, the Soviet Union soon began to compete with the Allies, especially the United States, by pursuing a policy of military and ideological expansionism (Kim, 1991, 19-24). The target of this expansionist policy concerned not just Eastern Europe, but the entire world. The Korean peninsula occupied a geopolitically vital location in the expanding Soviet empire’s security scheme, and naturally became a part of the Cold War conflict.

The United States, on the other hand, was busy at work re-ordering the world according to its own capitalist model. U.S. policymakers saw the Soviet-centered socialist bloc, the national and ethnic liberation of the Third World, and nationalization as chief obstacles to this imperial vision, and began to make efforts to contain and resist these movements. Shortly after World War II came to an end, the Roosevelt administration hurried into signing an agreement with the Soviet Union in which both sides agreed to contain the march of radical nationalism worldwide and aid in the self-determination of recently decolonized Asian nation-states (Kim, 1996, 89).

Although signs of escalating tension between the United States and the Soviet Union began to surface during World War II, Moscow nonetheless dispatched its troops to the Korean peninsula, seven days before Japan’s surrender, upon request from the United States. Japan conceded the war earlier than expected after the United States dropped nuclear bombs. The early surrender by the Japanese, the speedy dispatch of Soviet troops, and Washington’s strategy for the balance of power over the Korean peninsula finally culminated in both the decolonization of the Korean peninsula and its absorption into the Cold War against its will. The establishment of the USAMGIK immediately after the Japanese retreat enfolded the Korean peninsula in an identity crisis. The bipolar system of the Cold War also raised and deepened socio-structural and ideological conflicts in Korea, which served to solidify the regime of national division (Kim, 1992, 4-5).

In other words, the national crisis Korea experienced in the days after its decolonization was an outcome of a confluence of multiple factors, including, Washington’s strategic mistake of inviting the Soviet Union onto the Korean peninsula based on the U.S.’ overestimation of the tenacity of the Japanese; the Soviet Union’s unplanned, and lucky, involvement in Korean affairs and subsequent expansion of influence; Korea’s failure to achieve national liberation on its own; and the growing extremity and solidification of the right-left ideological divide in Korea which left its national liberation in the hands of superpowers. The national crisis engulfing Korea during this period thus involved ideological and territorial conflicts associated with the rise of the Cold War.

(2) Economic Crisis Involving an Abrupt Decline in Production and Soaring Inflation

The defeat of Japan and national liberation abruptly severed ties between the Korean and Japanese economies, the side effects of which included an abrupt decline in production and a soaring inflation rate. Accordingly, the total volume of imports and exports that stood at KRW 1.9 billion in 1944 rapidly plummeted to KRW 200 million in 1945.

The radical contraction of production caused a severe economic crisis in Korea. Assuming the grain output of the five years from 1935 through 1939 to be 100, the grain output of 1945 and 1946 fell to 74 and 71, respectively, while the industrial output of 1946 amounted to less than 30 percent of what it had been in 1939. By November 1946, there were approximately 1.1 million unemployed people, raising the unemployment rate to 12 percent. The decline in production alone left half a million people without jobs. The root cause for this abrupt drop in production was the sudden collapse of the colonial economic structure. The division of the Korean peninsula between the North and the South also compromised the stable supply of raw materials, while Koreans were incapable of securing either the infrastructure or the capital needed for industrialization.

In particular, the inflation rate reached an unprecedented rate in Korea during the USAMGIK period. The retail price multiplied 17-fold and the wholesale price 33-fold between August 1945 and the end of 1947. Wholesale and retail price indices had increased by 580 times and 560 times, respectively, since 1936. Soaring inflation represented the stark drop in output and the continued increase in population, and in part stemmed from the sudden increase in the amount of money in circulation. The Japanese colonial government had issued an additional KRW 3.7 billion for its liquidation immediately before retreating from Korea, while KRW 900 million had to be issued in addition for citizens who had returned to Korea with Japanese banknotes. Moreover, the spike in the grain price represented a severe threat to ordinary people.

(3) Explosion of Ideological Conflict and the Domestic Political-Social Crisis

In general, the absence of effective leadership or a ruling group tends to amplify and accelerate national crises (Kim, 1992). The leadership vacuum that existed in Korea post-liberation opened the door to fierce power plays by left and right-winged factions for control over the nascent nation. The situation naturally intensified the acuity of political, social, and ideological conflicts engulfing Korean society at the time. The confrontations between Yeo Unhyeong of the Korean Establishment Preparation Committee and Song Jinwoo of the Nation Foundation League, between the Korean Communist Party and the United National Party, between the Korean People’s Republic and the Provisional Government, and between Rhee Syngman and communists in general are representative of the deepening divide that was occurring in Korean society at large (Kim, 1996; 162).

The ongoing confrontation between the left and the right reached new heights in late 1945, early 1946 when Koreans began to debate the desirability and legitimacy of superpowers’ trusteeship over the Korean peninsula. The Conference of Foreign Ministers held in Moscow in 1945 turned the left in Korea in favor of the trusteeship and the right against it. The question of trusteeship thus added to the state of confusion that marked Korean politics and public discourse at the time.

The absence of cohesiveness and the raging ideological warfare in the social elite conspired with external pressures exerted by superpowers and the Cold War to fatally undermine Koreans’ nation-building project, and precipitated the division of the Korean peninsula between the North and the South, representing Soviet and American interests, respectively.

Source: Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2008. Korean Public Administration, 1948-2008, Edited by Korea Institute of Public Administration. Pajubookcity: Bobmunsa.

2. Changing Internal and External Conditions and National Crisis

The main actors in Korean politics after the country regained its liberty can be divided into three groups. The first group includes the United States and the Soviet Union, who were each competing for control over the Korean peninsula. While Japan and China were also significant state actors, their role in the unfolding of the national crisis in Korea was secondary to that of the United States and the Soviet Union. The second group included the members of the USAMGIK who were de-facto rulers of South Korea in its incipient years. The third group includes the various political factions and groups in South Korean society competing for dominance.

The Korean peninsula became a hotly contested ground in the evolving rivalry and conflict among these groups after its liberation from Japan. The basis for internal legitimacy was shattered as domestic social groups came to embrace external ideologies. The worldwide confrontation between capitalism and socialism took on an acute manifestation in Korea, with the animosity between the pro-Japan and anti-Japan sides giving way to fierce left-right competition over the building of a modern nation-state in Korea. The USAMGIK went on to repress radical political groups and put in place a powerful state system under the pretext of establishing a capitalist economic order and a political system for the Korean people. We may better understand the evolving dynamics among the main actors and the changing background situations by dividing the USAMGIK period into the early, middle, and final years.

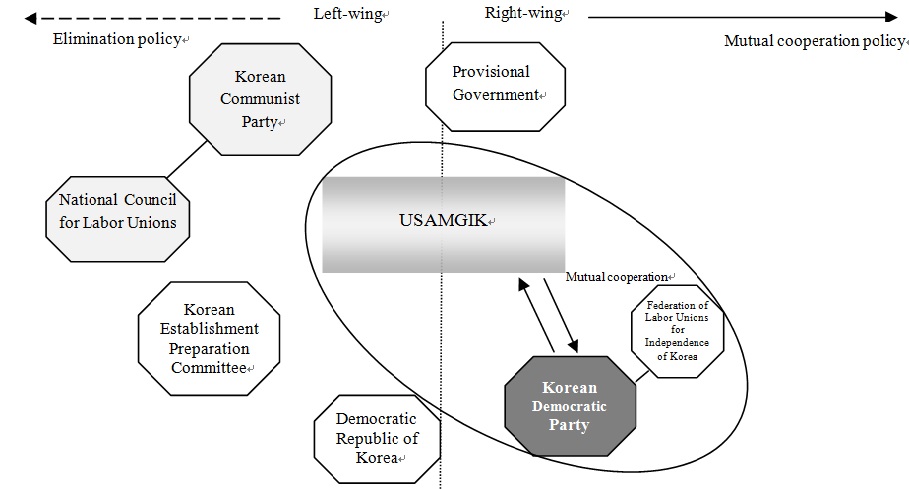

First, the USAMGIK came into being against the backdrop of intensifying competition among various ideological factions in Korea for dominance over the emerging state system. These factions included the left-leaning Korean Establishment Preparation Committee and the Korean People’s Republic, nationalist groups represented by the Provisional Government, and right-wing factions led by the Korean Democratic Party (KDP) and comprised of former collaborators of the Japanese colonial regime. The USAMGIK supported the KDP and appointed its prominent party members to various key positions. The USAMGIK felt compelled to build a strong ideological alliance with what it perceived to be loyal Koreans capable of countering the spread of radicalism and communism. The right-winged groups making up the KDP were, to the USAMGIK, perfect candidates for such an alliance. The KDP and its supporters had much at stake in preventing an anti-Japan government from coming into being in Korea, as such a government would demand the redistribution of land and the punishment of former collaborators of Japan (Kim, 1992, 191). Figure 4-2 illustrates this convergence of interests among the main actors in Korean politics during this period.

Second, the escalating controversy over the trusteeship of Korea in 1946 served to transform the cooperative relationship between the USAMGIK and the KDP. The USAMGIK was embarrassed by the shift in public opinion, as right-winged groups in Korea came to oppose the trusteeship, while left-winged groups favored it (Kim, 1992, 129). The USAMGIK could not risk violating the Moscow Agreement by continuing to support the KDP and right-winged groups. In an attempt to overcome this dilemma, the USAMGIK set out to discover and support moderates, led by a charismatic leader named Yeo Unhyeong. Table 4-1 lists the names of the representatives of right- and left-winged groups who took part in the Left-Right Collaboration Movement encouraged by the USAMGIK.

[Figure 2-2] Dynamics between the USAMGIK and Korean Social Groups after National Liberation

[Table 4-1] Representatives Participating in Negotiations for the Left-Right Collaboration Movement

| Faction | Name | Affiliation |

| Right | Kim Gyushik Won Sehun Kim Bongjun Ahn Jaehong Choi Dongoh |

Vice Chair, Democratic Council KDP Provisional Government National Party Member of Democratic Council, Vice Chair of National Emergency Council |

| Left | Yeo Unhyeong Heo Heon Jeong Noshik Lee Gangguk Seong Jushik |

Chief, People’s Party; Chair Delegation, Democratic National Front Chair Delegation, Democratic National Front New Democratic Party Communist Party Democratic Revolution Party |

| Source: Song, 1985, 327 | ||

The Left-Right Collaboration Movement, however, ended in vain due to the USAMGIK’s continued oppression of left-wing groups, the failure of both sides to make ideological concessions, and Yeo’s murder in July 1947. Yeo’s assassination catalyzed the realignment of political groups in South Korea. The center-left nationalist groups thus came to side with the extreme-left communists, while the right-winged groups came to join the extreme right-winged factions in their increasingly vocal demand for a single government on the Korean peninsula.[1]

Third, the formulation of the Truman Doctrine led the USAMGIK to reinforce its attacks on left-winged groups in Korea. In response to the increasingly hardline stance of the USAMGIK, the Korean Communist Party, the Democratic National Front, and other such groups concluded that peaceful and legal protests were no longer working. They thus countered the USAMGIK’s oppressive measures with the general strike of September 1947 and the violent people’s resistance and other campaigns that were launched in October of the same year. As Washington continued to pursue American interests in Korea and elsewhere by adopting a stronger anti-communist stance displayed in such initiatives as the Truman Doctrine, the relocation of the UN building, and the abandonment of President Roosevelt’s vision of trusteeship, the state of confusion escalated in Korean politics and finally led the KDP, helmed by Rhee Syngman, to emerge victorious. The election of May 10, 1947 resulted in the Pro-Rhee Council for Promoting the Independence of Korea and the KDP winning greatest number of seats in the National Assembly.

The USAMGIK, born amid the early tumult of the Cold War, contributed to the consolidation of national and territorial division on the Korean peninsula by inhibiting the autonomous political activities of domestic groups. The USAMGIK also catalyzed the realignment of political groups in Korean society while serving as the de-facto supreme command over Korea in the first years of decolonization. Left-leaning groups, which garnered the most support from Koreans at the time of national liberation, gradually lost power at both the local and central levels. In the meantime, once-vulnerable right-winged groups were able to consolidate their claim to power first by serving in an advisory capacity for the USAMGIK, and later by dominating the newly born republican government of South Korea (Goh, 1990, 427). The actions of the USAMGIK would go on to exert a profound and irreversible impact on the development and overall operations of public administration in South Korea.

[Figure 4-3] Dynamics between the USAMGIK and Korean Social Groups in the Later USAMGIK Period

Source: Korea International Cooperation Agency. 2004. Study on Development Aid and Cooperation for South Korea: Size, Scope and Exemplary Effects. Seoul.

IV. Changes in the Administrative System under the USAMGIK

1. Institutional Changes in the Administrative Organization

The USAMGIK inherited the administrative organization and bureaucratic practices of the Government General of Joseon in their entirety, directly ruling Korea while at the same time keeping the country in a state of military occupation. The first and foremost principle the USAMGIK adopted in reorganizing the governance structure of Korea was centralization, which was necessary to facilitate the U.S. Commander’s control over the country. The changes that took place in the Korean administrative organization during the USAMGIK period can be divided into three phases. The first phase for the most part retained the Government General’s administrative organization; the second phase saw the USAMGIK make its first attempts toward an innovative administrative organization; and in the third phase the USAMGIK pursued partial reforms to the second-phase organizational structure and began efforts to transfer governing power to the First Republic (Shin, 1997, 66). Table 4-2 summarizes the important details of these changes.

| [Table 4-2] Changes in the Administrative Organization under the USAMGIK | ||

| Phase 1 | Began with USAMGIK’s acquisition of Government General of Joseon (with Governor General’s surrender) on September 9, 1945, and ended with the renaming of government departments on March 29, 1946. | |

| Early | January 4, 1946: official establishment of USAMGIK (US Forces to Korea de-facto ruler until this date). ※ Each bureau was given a single American head. |

|

| Later | Period after official establishment of USAMGIK on January 4, 1946. ※ Beginning in December 1945, each bureau was co-headed by an American and a Korean. |

|

| Phase 2 | Began with the renaming of government departments on March 29, 1946, and ended with the establishment of the South Korean Interim Government on June 3, 1947. | |

| Early | Period until appointments of American and Korean co-heads to bureaus on February 15, 1947. | |

| Later | Period after appointments of American and Korean co-heads to bureaus on February 15, 1947. | |

| Phase 3 | Began with the establishment of the South Korean Interim Government on June 3, 1947, and ended with the birth of the Government of the Republic of Korea on August 15, 1948. ※ Administrative powers transferred on September 13, 1948. |

|

| Source: Shin, 1997, 66 | ||

Source: Ministry of Government Administration, 1980: 90.

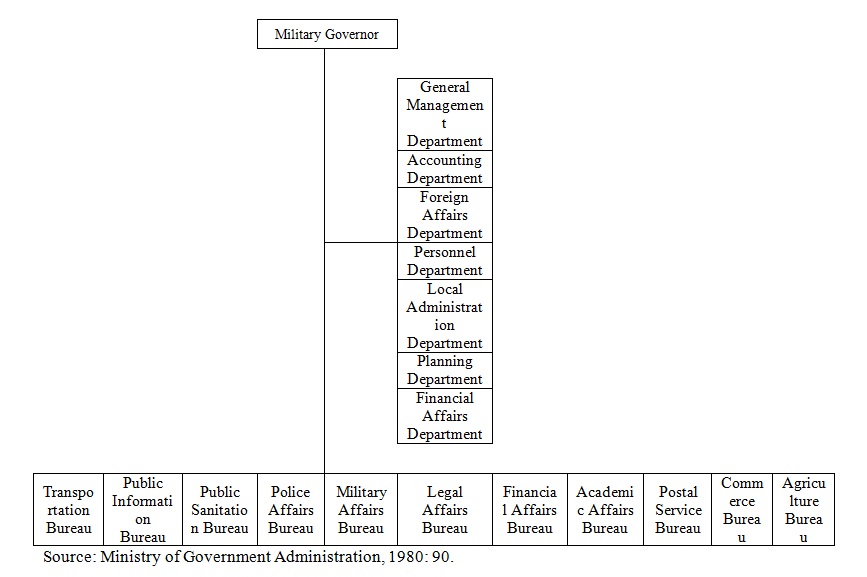

[Figure 4-4] USAMGIK Organization (1945.9-1946.3)

During Phase 1, the USAMGIK retained the administrative organization of the Government General of Japan almost intact.[1] As Figure 4-4 shows, the administrative organization during this period consisted of seven departments and eight bureaus. The seven departments were divided by function, i.e., general management, foreign affairs, personnel, planning, accounting, local administration, property management, etc. The eight bureaus were also divided by function, i.e., police affairs, financial affairs, mining and manufacturing, academic affairs, agriculture and commerce, legal affairs, postal service, and transportation. The USAMGIK added to this organization three additional bureaus for public sanitation, military affairs, and public information. It also renamed the Bureau of Mining and Manufacturing and the Bureau of Agriculture and Commerce as the Bureau of Commerce and the Bureau of Agriculture, respectively, thus maintaining 11 bureaus in total.

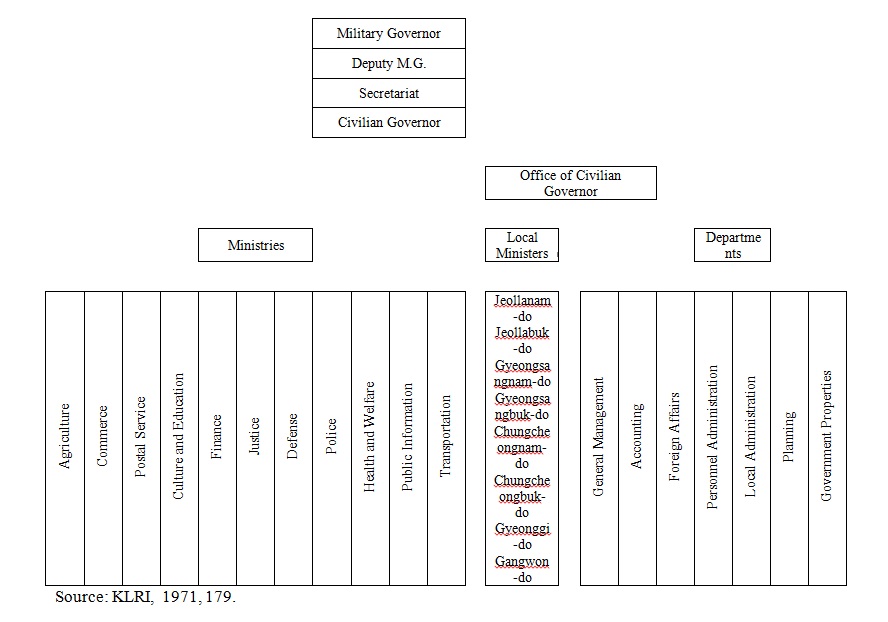

In March 1946, the USAMGIK changed the bureau system to a ministry system according to USAMGIK Decree 64. As Figure 4-5 shows, the Bureau of Academic Affairs accordingly became the Ministry of Culture and Education; the Bureau of Legal Affairs, the Ministry of Justice; the Bureau of Transportation, the Ministry of Transportation; the Bureau of Military Affairs, the Ministry of National Defense. The bureaus of police affairs, agriculture, commerce, financial affairs, postal service, and public sanitation were similarly changed. The seven departments were converted into seven offices, including the Public Personnel Administration Office, the Local Administration Office, the Food Administration Office, the Price Administration Office, the Public Property Management Office, the Foreign Affairs Office, and the General Management Office. The ministries of civil engineering and labor were added and the Local Administration Office was closed down later, bringing the organization to 13 ministries and six offices in total. Throughout Phase 2, the USAMGIK also strengthened and centralized its functions and powers.

Source: KLRI, 1971, 179.

[Figure 4-5] USAMGIK Organization (as of March 29, 1946)

In June 1947, the USAMGIK was renamed as the South Korean Interim Government, and the Organizational Reform Committee (ORC) was newly created. The ORC reorganized the administrative system into 13 ministries and one special bureau (in the place of the six abolished offices), and also additionally created the Personnel Committee and the Central Economy Committee, the latter of which was put in charge of overseeing the Price Administration Office and the Food Administration Office. This new organizational structure remained intact until the official government of the Republic of Korea finally came into being in August 1948 (Kim, 1996, 228). The main objective of this third phase of administrative reform was to enhance the government’s control over economic aspects by introducing the two new offices.

The USAMGIK initially judged it more economical and rational to maintain the governance structure of the Government General of Joseon, from which it pursued incremental changes later on. This inherited structure also provided the context in which the USAMGIK sought to introduce a limited measure of democracy into Korea, particularly by dividing the Korean government into three branches, including the South Korean Transitional Legislature and the Supreme Court (with the appointment of the Chief Justice). In its last days, the USAMGIK made more frequent and complex attempts at reform, expanding the overall organization significantly. Yet it also retained the tendency toward centralization by expanding the central administrative organization to a greater extent than its local counterparts.

It was indeed under the USAMGIK that the pattern of centralization began to accelerate in Korea, with the central administrative organization expanding, the number of province-stationed civilian agents (not part of the tactical forces) increasing, and the former Government General tasks of local administrations being transferred to the central government. While the USAMGIK retained the relatively decentralized administrative structure of the Government General of Joseon until April 1946, the trend of centralization was afoot in almost all ministries and offices by 1947. Local administrative organizations that had formerly served as buffers between the central government and local units were all but abolished by April 1946. Local administrations thus turned into local offices of the USAMGIK without any independent legislative powers or say in central policymaking (Mead, 1951, 80-81, as quoted in Kim, 1992, 25). Local administrations thus lost the power of self-government.

Though the USAMGIK inherited the Government General of Joseon’s administrative structure (under Decree 21 of November 2, 1945), it did make some changes to it. Decree 60 issued on March 24, 1946, called for the abolishment of local legislatures and school councils at the levels of provinces, towns, eup, myeon, and islands. The USAMGIK also re-drew administrative districts, rearranging counties, villages, myeon, eup, and cities near the 38th Parallel border (under Decree 22 of November 3, 1945), and separated Seoul from the province of Gyeonggi-do, turning the former into a special (capital) city and granting to it the same range of functions and powers as those granted to provinces (under Decree 106 of 1946). The Charter of Seoul was closely modeled after the charters of American cities, and represented the first official attempt to introduce at least a measure of self-government in Korea. The USAMGIK also renovated other administrative offices including those of provincial governors, the Mayor of Seoul, vice mayors, county mayors, island magistrates, eup and myeon leaders, and the like, and redesigned special administrative units reporting directly to central government agencies.

| Military Governor | ||||||

| Minister of Civil Affairs | ||||||

| Ministry of Police | Ministry of Justice | Ministry of Culture and Education | Ministry of Commerce | Ministry of Finance | Ministry of Postal Services | Ministry of Health and Welfare |

| General Management Bureau; Public Security Bureau; Education Bureau; Investigation Bureau; Communication Bureau |

General Management Bureau; Lawyers Bureau; Court Bureau; Prosecutors Bureau; Penal Bureau; Petitions Bureau; Legal Basics Bureau; Legal Investigation Bureau |

General Management Higher Education Bureau; Basic Education Bureau; Rehabilitation Bureau; Publishing Bureau; Adult Education Bureau; Meteorology Bureau |

General Management Bureau; Mining Bureau; Commerce Bureau; Trade Bureau; Industry Bureau; Auditing Bureau; Patent Bureau |

National Treasure Bureau; Investment Bureau; Office Bureau; National Bank Bureau; Accounting Bureau; Accounting Inspection Bureau; Government Monopoly Bureau |

General Management Bureau; Telegraph Bureau; Postal Service Bureau; Savings Deposit Bureau; Finance Bureau; Equipment Bureau; Postal Service School |

General Management Bureau; Aid Bureau; Housing Bureau; Medical Bureau; Preventive Medicine Bureau; Dentistry Bureau; Surgery Bureau; Pharmaceutical Bureau; Nursing Bureau; Natal Care Bureau; Gynecology Bureau; Analysis Bureau; Welfare Facility Bureau; General Welfare Bureau |

| Civil Engineering Dept. | Public Security Department | Reunification Department | Agriculture Department | Labor Department | Transportation Department | Foreign Affairs Office |

| General Management Bureau; Public Works Bureau; Irrigation Bureau; Urban Bureau; Land Survey Bureau |

Public Opinion Bureau; Public Information Bureau; Broadcasting Bureau; Publishing Bureau; Projects Bureau |

National Defense Guard Supreme Command; Coastal Guard Supreme Command; National Defense Guard Central Training Center; Military Language School; Supply Department (Clothing Depot) |

Agriculture Bureau; Fishery Bureau; Agricultural Economy Bureau; Forestry Bureau |

Labor Affairs Bureau; Labor Planning Bureau |

Railway Transportation Bureau; Marine Transportation Bureau; Public Transportation Bureau; Aviation Bureau |

General Management Bureau Foreign Affairs Division |

| Food Administration Office | Price Administration Office | Public Property Management Office | Administrative Office | Public Personnel Administration Office | ||

| Planning and Management Division; Food Rationing Division; Food Statistics Division |

General Management Division; Inspection Division; Administration Division |

General Management Division; Planning Division; Inspection Division; Investigation Division ; Documents Division |

General Management Division; Research Division; Production Accounting Division; Planning Division; Construction Division; Statistics Division |

General Management Division; Civil Service Examination Division; Appointment Division; Duty Division; Investigation Division; Training Division; Education Division |

||

[Figure 4-6] Central Administrative Organization under the South Korean Interim Government (July 1947)

Source: Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2008. Korean Public Administration, 1948-2008, Edited by Korea Institute of Public Administration. Pajubookcity: Bobmunsa.

In the early months the USAMGIK’s reliance on the Government General of Joseon extended beyond organizational structure to include the latter’s bureaucrats, laws, rules, decrees, public announcements, and official records. Between October and December, 1945, almost 75,000 bureaucrats of the Government General were on the USAMGIK’s payroll, including some re-hired bureaucrats (Kim, 1992, 194). KDP members also occupied key positions in the government, particularly in advisory councils and in the ministries and departments of central and local administrative organizations, exerting a great influence.

The USAMGIK applied a series of criteria in recruiting additional personnel (Kim, 1996, 238-242). First, candidates had to be proficient in the English language, well-educated, and pro-America, and were expected to support liberal values. Second, Koreans with any ties to communism were excluded at the outset. The USAMGIK insisted on these principles as essential to the U.S. fight against the Soviet Union and communism, and dutifully excluded members of the Korean Communist Party and their sympathizers from its expanding organization. As the KDP naturally provided the greatest pool of candidates meeting these criteria, the USAMGIK filled numerous positions in its organization with members of that party. Between December 1945, when the USAMGIK began to appoint American leaders to ministries and departments along with their Korean counterparts, and March 1946, when indirect rule began, several KDP members were appointed to important positions and departments in the USAMGIK, as shown in Table 4-3.

[Table 4-3] KDP Members in Key Positions in the USAMGIK

| Organization | Rank/Title | Name | Organization | Rank/Title | Name |

| Supreme Court | Supreme Court Director | Kim Yongmu | Ministry of Police | Police Administration District 5 | |

| President | Roh Jinseol | Vice Director of Administration | Kang Suchang | ||

| Chief Prosecutor | Gu Jagwan | Public Security Division Chief | Lee Manjong | ||

| District Court Director | Yun Myeongryong | Security Division Chief | Park Chanhyeon | ||

| Attorney General | Lee In | Information Division Chief | Kim Heon | ||

| Ministry of Justice | Minister | Kim Byeongno | Women Police Division Chief | Hwang Hyeonsuk | |

| Office of Legislation Director General | Kwon Seungryeol | Office of Foreign Affairs | Director General | Mun Janguk | |

| Court Director | Kang Byeongsun | Ministry of Culture and Education | Minister | Yu Eokgyeom | |

| General Management Bureau Director | Kim Yongwol | Education Department Head | Choi Seungman | ||

| Administration Bureau Director | Choi Byeongseok | Public Personnel Administration Office | Director General | Jeong Ilhyeong | |

| Ministry of Police | Minister | Jo Byeongok | Ministry of Labor | Minister | Lee Hungu |

| Capital Police Force Chief | Jang Taeksang | Ministry of Health | Minister | Lee Yongseol | |

| Public Security Chief | Ham Daehun | Price Administration Office | Director General | Choi Taeuk | |

| Jeju Inspection Chief | Kim Daebong | ||||

| Source: Shim, 1984, 56-57 | |||||

The Administrative Advisory Council (AAC) set the basic rules and principles of the USAMGIK’s personnel recruitment policy. Military Governor Archibald Arnold set up the AAC on October 5, 1945, and 11 Korean citizens sat on the Council. Of these 11 members, all but two (Yeo Unhyeong and Cho Mansik) were members of the KDP. The USAMGIK also recruited KDP members to a great number of high-ranking posts in local organizations, the military, and the police administration in an attempt to enhance the legitimacy of its rule.

It was not until March 29, 1946 when the Military Governor’s Staff was renamed and converted into the Public Personnel Administration Office that the USAMGIK began to introduce American elements into the personnel organization and policy. The Rules on the Functions of the Public Personnel Administration, proclaimed as Decree 69 on April 20, 1946, officially endorsed the meritocratic principle, and charged the newly created office with preparing and developing the civil service system and elements of scientific public personnel management in post-liberation Korea (Kim, 1992, 261).

In the process of redesigning the public personnel administration system, the USAMGIK introduced a series of modern American measures without much regard for the tradition and reality of bureaucratic practice in Korea. The American elements introduced during this period included the position classification system, the meritocratic principle, and the open competition (examination) system. The position classification system, in particular, marked a fundamental shift in the public personnel administration system from the days of the Government General of Joseon. Bureaucratic positions were divided into four types: clerking, administrative, and financial (CAF) positions; professional and technical (P&T) positions; training, defense, and storage positions; and specially appointed positions. In addition, the USAMGIK instituted various other measures to enhance the meritocratic nature of civil service, including the performance scoring and evaluation system; general duty standards; remuneration and promotion criteria; and preliminary, on-the-job, and promotion training.

While these new measures were introduced with positive and innovative outcomes in mind, they failed to produce the intended effects since Korean society was still in the throes of extreme ideological conflict ignited after the country’s liberation. These measures were not only imposed in a top-down manner without much regard for Koreans’ willingness or traditions, but there was also a dearth of people trained and capable of seeing them through (Kim, 1996, 292). The legal requirements of open competitive examinations and other such recruitment measures were not strictly observed, as the USAMGIK itself appointed the majority of officials by decree. This practice, intended to block communist infiltration into the government organization, eventually led the KDP to monopolize key positions.

Nevertheless, the American elements of the public personnel administration introduced in Korea by the USAMGIK during this period did eventually generate radical changes. The principles of democracy and merit in public personnel administration would inspire policymakers in the First Republic of Korea to devise a more professional and efficient system of career bureaucracy in the later years.

3. Introduction of a Democratic System

To root the concept of liberal democracy in Korea, a nation ruled by a king for the preceding five centuries and then by Japanese colonialists, the USAMGIK introduced various features of American democracy, including legislation, elections, and party politics. The ostensible goals of these changes were the liberalization of Korea, the democratization of its political organizations, and the eventual realization of an autonomous and independent Korean nation. In fact, however, the USAMGIK’s harsh anti-communist stance in the name of democracy inhibited Koreans’ right to choose their own governing ideology. It was thus under the USAMGIK that democracy came to be equated with anti-communism in Korea. The democratic measures that the USAMGIK introduced in Korea during this period did, however, form the basis of Korean political institutions later on.

The principles of democratization announced by the USAMGIK effectively capture and sum up the essential features and attributes of Western democracy.

| Principles of Democratization under the USAMGIK 1. Political authority shall originate with the people. 2. In exercising political authority and making policies, policy issues shall first be submitted for the people’s approval or disapproval, in the form of free elections. 3. Elections shall be competitive, featuring candidates from multiple parties. 4. Political parties shall be democratic and voluntary associations of the people. 5. The basic civil rights of the people shall be guaranteed. 6. Channels of public opinion shall be guaranteed freedom from government control. 7. The rule of law shall be recognized. 8. The government and the structure of power exercised shall be decentralized. |

The democratic measures the USAMGIK introduced according to these principles can be summarized as follows (Kim, 1996, 325-346). First, the USAMGIK did succeed in establishing an interim legislature in South Korea; it may not have been the most advanced and modern kind, but it was a legislature nonetheless. While the legislature officially and institutionally represented Koreans, it was, in substance, a mere advisory council, which the Governor of the USAMGIK consulted when he exercised his rights of ratification and veto. The legislature was undeniably subjugated to the USAMGIK, and the USAMGIK used it to maintain a certain quota of Korean officials in its midst and also to maintain and strengthen its grip on governance. The legislature and the political parties employed were primarily used to silence opposing voices and resistance in society at large. With anti-communism reigning supreme as the governing ideology, the legislature was rather used to justify the irreversible division of the Korean peninsula.

Second, Korea became acquainted with the modern system of elections under the USAMGIK, which organized elections for the members of the interim legislature it had set up. Although the first elections organized by the USAMGIK drew very limited participation, the USAMGIK and the KDP were nonetheless able to use these elections to legitimize their power and rule.[1]

Third, the USAMGIK introduced the modern party system in Korea, allowing Koreans, at least in theory, to form political associations freely and giving structure to Koreans’ participation in democratic politics. The USAMGIK required that these political parties be registered for monitoring and control. The number of political parties that were registered with the Public Information Bureau and provincial administrations thus multiplied from 107 in 1946 to 397 in 1947. The political associations registered during this period included the Korean Establishment Preparation Committee, labor unions for various industries and trades, farmers’ groups, youth groups, women’s groups, academic societies, cultural associations, athletic organizations, and alumni associations.

Fourth, the USAMGIK set up various administrative committees, a classic feature of the American democracy, to facilitate democratic decision making. The administrative committees founded during this period and continuing to this day (albeit under different names) included the Central Economy Committee, which coordinated the policy plans and other related activities of all governmental ministries and departments pertaining to the Korean economy; the Joseon Economic Advisory Council, which provided advice upon request from the Governor and the Central Economy Committee; the Central Labor Conciliation Committee, which sought to protect workers’ rights and coordinate policies on labor disputes; the Joseon Education Committee, which provided advice on educational policy; the Education Review Committee, and others. The National Government Organization Act of the First Republic solidified these administrative committees as permanent features of Korean governance.

Fifth, the USAMGIK reorganized its structure on March 29, 1946, renaming the Legal Affairs Bureau as the Ministry of Justice, thus acknowledging the independence of legal and judicial affairs from the government at least officially. However, it was not until the last days of the USAMGIK that jurisdiction over court administration matters was transferred from the Ministry of Justice to the Supreme Court and the independence of the judiciary was completely institutionalized. Nevertheless, it was the USAMGIK period that led to the creation of the framework in Korea for the separation of powers by introducing a national legislature and acknowledging the independence of the judiciary.

Source: Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2008. Korean Public Administration, 1948-2008, Edited by Korea Institute of Public Administration. Pajubookcity: Bobmunsa.

1. Economic Policies

By the time the USAMGIK came into being, South Korea was embroiled in an economic crisis of an unprecedented scale amid an increasingly tumultuous political environment. South Korea lagged far behind North Korea in terms of industrial development. In the face of soaring prices and extreme food shortages and poverty, theft, smuggling, and other forms of violence and cruelty rose to alarming heights throughout Korean society. The USAMGIK initially sought to introduce the American-style market economy in Korea in an attempt to stabilize and improve the Korean economy. But the firestorm of ideological and social conflicts that had taken over South Korea prevented the effective transplant of the market economy onto Korean soil. The USAMGIK did, however, make some genuine efforts to achieve a semblance of fair trade and market economy in Korea. The key economic problems the USAMGIK needed to solve urgently were how to handle formerly Japanese-owned properties that formed over 80 percent of the gross domestic product of Korea at the time, and how to go about distributing U.S. foreign aid and grants in Korea.

(1) Managing Formerly Japanese-Owned Properties

At the time of Korea’s liberation, the Japanese owned 94 percent of all assets in the country’s manufacturing sector. The USAMGIK absorbed and managed most of these assets upon Korea’s liberation (Kim, 1990, 435). The policy the USAMGIK employed in handling these properties informed the principles for new businesses and corporations in post-liberation Korea and contributed to the development of a basic framework for the later Korean market economy.

But the policy was not without controversy. The USAMGIK appointed numerous opportunists and former collaborators of the Japanese colonial regime to dispose of and manage these properties, and the legacy of this choice continues to be a thorny issue in Korea, even today. More specifically, the process by which the USAMGIK absorbed, managed, and disposed of formerly Japanese-owned properties helped to generate a class of Korean financiers, and elevated the status of small shareholders, small vendors, and family businesses into the dominant ruling class. The multi-enterprise Korean conglomerates known as chaebol also have their origins in these properties. The USAMGIK’s policy of managing and redistributing these properties additionally gave birth to the corruption-prone and less than fair partnership between politics and businesses, which remains in place to this day. The KDP, led by Rhee Syngman, had a major say in deciding the management and disposal of these properties, which thus ended up solidifying the KDP’s hold over the country (Kim, 1996, 362).

(2) Managing Foreign Aid and Grants

Washington began to provide economic aid and grants for Korea via the USAMGIK through the Government Appropriations for Relief in Occupied Areas (GARIOA, established 1945). This foreign aid plan continued in Korea until 1971, amounting to USD 5.7 billion. The USAMGIK had an aid budget of USD 500 million, with food, clothing, medical supplies and the like claiming 50 percent or so of that budget in 1945 (dropping to 43 percent by 1948), while raw materials for production, such as fertilizers, claimed the remaining 50 percent (Krueger, 1979, 18).

Washington provided foreign aid and grants primarily out of military and political motivation, i.e., the goal of keeping Korea from the reach of communism, and was less concerned with the economic and industrial impact of the help it provided. Just as certain individuals and their associates were favored in the process of redistributing Japanese-owned properties, the same individuals and their associates again benefited disproportionately from the USAMGIK’s distribution of grants and aid from Washington. Although this support deepened the already cozy relations between politics and businesses in Korea, it also undeniably helped to maintain a minimum standard of living for the majority of Koreans, rein in the soaring inflation, and stabilize the Korean economy in general.

(3) Instituting Land Reforms

Having acquired Japanese properties and land, the USAMGIK proceeded with its land reform plan, which allowed once destitute sharecroppers to become property owners. At the time of Korea’s liberation, the total area of land distributed to farmers amounted to 16.7 percent of all farming land available in South Korea, benefitting 27 percent of farming households (Lee, 1981, 109-110). The USAMGIK also exhorted the interim legislature to enact legislation for land reforms concerning farmland areas other than those left behind by Japanese owners (Kim, 1992, 434). The reform of the formerly Japanese-owned farmland appears to have provided the primer for the Korean legislation, enacted in March 1950, on the redistribution of farmland in general in Korea. These farmland reforms boosted the democratic aspects of the rural economy and also elevated the station of farmers in general significantly.

The design for the USAMGIK’s land reform policy came from the U.S. Department of State, which, aware of the growing ideological rivalry in Korea, sought to disable left-winged groups in Korea from instigating and mobilizing the popular masses, including farmers, by turning farmers into conservative property owners. The main objective of these land reforms was thus mitigating the political, economic, and social forms of inequality originating from the existing pattern of land ownership, and thereby enhancing the legitimacy of the transitional government (Kim, 1996). Although these land reforms initially ran into opposition from the KDP and the landholding class, the USAMGIK resolutely implemented these reforms, thus setting a model of the modern state as a distributor of wealth. These land reforms succeeded in enhancing the political stability of rural communities, which later translated into unquestioning support for the First Republic.

2. Social Policies

The USAMGIK reinforced the security-related state apparatus in an effort to maintain law and order in an increasingly tumultuous and ideologically strained society, strengthening the government’s control over labor groups, farmers, and the press in particular. The USAMGIK’s efforts to maintain social order also included the launch of educational reforms.

(1) Labor Policy

The USAMGIK promulgated the Decree on the Protection of Workers (USAMGIK Decree No. 19) on October 30, 1945, and the Public Policy on Labor Issues (USAMGIK Decree No. 97) on July 23, 1946. These two decrees aimed at freeing workers from the past four decades of servitude and bondage as a matter of national emergency; providing legal guarantees for the rights of individual workers and labor groups to seek employment and work without unjustified interference; and giving the Labor Conciliation Committee the authority to settle disputes over working conditions (Kim, 1992, 323). The decrees also legalized labor unions. The USAMGIK then went on to enact Korea’s first legislation mandating democratic labor relations. This legislation has structured all subsequent legislation on labor relations until now.

South Korea suffered under abject poverty and intensified social conflicts in the immediate aftermath of its liberation from Japan. Workers regularly and actively took to the streets in desperate attempts to secure their livelihoods. The USAMGIK, however, instead of accommodating the workers’ demands, reacted to these activities with increasing levels of violence and oppression. The USAMGIK adopted an uncompromising stance of control against labor unions affiliated with the national federations of left-leaning labor groups, and sought to counter the rising popularity of these organizations by setting up a labor union of its own, i.e., the right-leaning Korean Federation of Labor Unions for Independence. The USAMGIK’s labor policy, in other words, traversed a thin line between these contradictory aspects. The USAMGIK recognized the need to introduce and uphold elements of liberal democracy in its labor laws, however passive and perfunctory they were, even while strengthening its oppressive control over labor activities. This widening discrepancy between the letters of the labor laws and their practice came to characterize the USAMGIK’s labor policy (Kim, 1996, 411-413).

(2) Press Relations

In a press conference held on September 11, 1945, Lieutenant General John Reed Hodge explained the USAMGIK’s basic approach to governance as follows (Choi, 1970, 83-89):

The freedom of the press that we are introducing into Korea literally means what it says. The U.S. government makes no interference whatsoever with the press. I am aware how the experience with Japanese imperialism has hurt the Korean press. The freedom of the press serves its purpose when it tells the truth to the public…. However, we will be compelled to take appropriate measures when the press threatens public security and order.

Hodge’s remark barely guise the real, twofold aim of the USAMGIK, which was to guarantee freedom and even support members of the press whose interests aligned with those of the United States, and to discriminate against, control, interfere with, and regulate others that disagreed with U.S. policies. The USAMGIK did in fact provide full protection and support for right-winged newspapers that were ideologically in harmony with the United States, while controlling and censoring left-leaning ones. The USAMGIK, in other words, acknowledged the freedom of the press only insofar as the press supported American interests and ideology. This repressive approach to left-leaning journalists and newspapers was evident in the legal actions taken against them. In the first two years of the USAMGIK, there were 3,546 cases tried by the Prosecutors’ Office against the press, with 4,312 journalists and related parties rounded up in relation to these cases.

(3) Education Policy

The USAMGIK strove to establish a whole new education system that denied the discriminatory undertone of traditional Korean education, and actively promoted egalitarianism with built-in institutional mechanisms for guaranteeing equal opportunity. The USAMGIK’s concern was evident in legislation it pushed to enhance the autonomy of Korean education, including those on the Koreanization of the educational system, the development of new curricula, the compilation and publication of textbooks in the Korean language, the re-training of teachers, the implementation of local self-administration on education, and others (Kim, 1992, 315-316).

The educational policy that unfolded under the USAMGIK went on to profoundly alter and shape subsequent Korean educational policies and contents, and exerted far-reaching influences on the development of Korean society in general, in both positive and negative ways. The three years of the USAMGIK resulted in the completion of the basic structure of modern education in Korea. Examples include the democratic and humanitarian spine of the Korean curricula; the division of school years into six years of elementary education, three years of junior high schooling, another three years of high schooling, and four years of university; the mandatory nature of elementary education; and university systems and rules modeled closely after American ones.

The USAMGIK educational policy served as an effective tool of socialization and ideological vaccination against communism, and played a crucial role in keeping intact newly introduced democratic systems and the new ruling elite. The American system of education, furthermore, went on to raise the educational attainment of the general public at large, and legitimized and perpetuated the reign of capitalism throughout society. Most importantly, it helped to dissolve the inequality of opportunity and education in Korea by mandating elementary education for all Koreans, which led to an increase in the proportion of Koreans completing secondary and higher learning (Kim, 1996, 436-438).

Source: Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2008. Korean Public Administration, 1948-2008, Edited by Korea Institute of Public Administration. Pajubookcity: Bobmunsa.

VI. Assessment of Institutional Changes in Korea under the USAMGIK

Table 4-4 categorizes and summarizes the changes in the administrative institutions and policies of the USAMGIK according to the analytical framework introduced at the beginning of this study.

| [Table 4-4] | Types and Attributes of Institutional Changes under the USAMGIK | |||

| Type | Institutions affected | Attributes | Type of change | |

| Political and administrative institutions | Administrative bodies | Central | *Phase 1: USAMGIK inherited Government General of Joseon’s administrative structure in entirety, believing that institutional continuity was necessary to minimize confusion and maximize governance efficiency. *Phase 2: New ministries and offices were created and tendency toward centralization set in. *Phase 3: New bodies were added to enhance economic policy, including Central Economy Committee, Food Administration Office, and Price Administration Office. *Gradual and incremental changes based on government organization inherited from Japanese colonial regime. |

Path-dependent change (Path Ta) |

| Local | *USAMGIK inherited Government General of Joseon’s local administrative structure in entirety, minus functions for colonial rule. *The dissolution of local administration began to accelerate the pattern of centralization. |

|||

| Personnel | Recruitment | *Bureaucrats of Japanese colonial regime were retained in early period of USAMGIK. *KDP members came to occupy high-ranking posts. |

Path-dependent change (Path Ta) |

|

| Personnel administration | *Modern and American personnel administration was introduced, disregarding tradition and practice. *Newly introduced elements included meritocracy, open competitive examinations, position classifications, etc. |

Radical change (Path Tb) |

||

| Democratic political institutions | *South Korean Transitional Legislature was established to introduce legislative politics. *Elections were introduced. *Free party politics and activities were instituted. *Administrative committees were set up to facilitate consensus-oriented, democratic decision making. *Independence of the judiciary was established. *Major features of Western democracy were thus grafted into the Korean political environment. |

Radical change (Path Tb) |

||

| National policies | Economic policies | Japanese-owned properties | *The properties of Japanese colonialists were redistributed in such a way that informed later Korean businesses and the market economy. | Radical change (Path Tb) |

| Foreign aid and grants | *USAMGIK’s plan of foreign aid and grants sought to minimize economic and social crises, e.g., abrupt inflation, food shortages, etc. *Ultimately helped to stabilize post-liberation Korean economy. |

|||

| Land reforms | *Japanese-owned farmland was redistributed to promote the stability and democracy of rural economies. *Prompted reform in the distribution of other farmland as well. |

|||

| Social policies | Labor | *USAMGIK introduced democratic laws on labor relations and legalized labor unions. *In reality, however, it oppressed labor activities. Much discrepancy between law and practice was noted. |

Radical change (Path Tb), accompanied by continuing oppression of left-leaning labor groups | |

| Press | *In principle, USAMGIK advocated freedom of the press. *In reality, USAMGIK protected and supported right-winged newspapers, while repressing and censoring left-winged ones. It was a discriminatory policy in practice. |

|||

| Education | *USAMGIK denied the validity of traditional, discriminatory education and promoted equal opportunity. *Influence of USAMGIK’s education policy continues today. |

Radical change (Path Tb) |

||

Amid the social chaos indicative of identity, ideological, and economic crises, the USAMGIK introduced radical changes by transplanting American-style capitalism and democracy onto Korean soil. In all areas of Korean society including the economy, unfamiliar systems purporting to realize unfamiliar values—namely, democratization and liberalization—were established. But notably, when it came to the recruitment and administration of public personnel, the USAMGIK relied on the organizational structure and bureaucrats of the Government General of Joseon, thus departing from the principles of democratization and decentralization characterizing American politics. The USAMGIK accepted the organizational structure of the Government General mainly because it perceived institutional continuity as a means of ensuring effective control and governance over the country.

As a result, the tendency toward the excessive growth of state apparatuses that began with bureaucratic and security expansions under the Japanese occupation remained intact during the USAMGIK period as well. The centralizing and repressive attributes of this administrative structure were especially evident in the control and censorship applied by the USAMGIK to the general public and to left-winged groups in particular. Fighting the Cold War and recognizing the need to contain communism to the north of the 38th Parallel, the USAMGIK also made efforts to establish democracy and capitalism in South Korea, introducing American-style institutional features and changes, including democratic political systems, the market economy, and egalitarian education.

The principal source of these changes was the United States itself, which instructed the USAMGIK in all its activities. All policies and actions of the USAMGIK reflected the external threats perceived by Washington and the measures it deemed necessary for pursuing and maximizing American interests. It was American perceptions and policies on domestic and international conditions that fundamentally realigned political groupings in Korea. Right-winged groups in Korea at first failed to gain popularity and power. Yet they came to occupy key posts and eventually formed the ruling elite after the USAMGIK came to power precisely because Washington and the USAMGIK exerted powerful influences on Korea as it struggled with the aftermath of decolonization. Washington thus directly controlled and shaped political and military developments in Korea via the MacArthur Command, the Occupied Country Command, and the USAMGIK.

The majority of radical changes that took place under the USAMGIK involved the introduction of the formal institutions necessary to prompt the growth of the market economy, civil society, and democracy. In order for these transplanted institutions to evolve in paths similar to those already seen in the advanced democratic states of the West, the rights and freedoms of the individual had to be respected and the fairness of the market economy ensured. This, in turn, required that the government minimize its intervention in the market and avoid direct control of society.

The contradiction between new democratic measures, on the one hand, and the repressive bureaucratic structure and apparatuses inherited from the Japanese colonial regime, on the other, persisted throughout the USAMGIK period. The stifling measures used against left-leaning groups also continued to grow in intensity. The USAMGIK, in other words, established and consolidated a culture of active state intervention and centralization, even as it fostered the market economy and civil society in Korea.

The contradiction among these different institutions and tendencies led to the formation of certain tensions and dynamics among them, ultimately affecting the ways in which those institutions evolved. The relative strength and autonomy of the state and bureaucratic apparatuses vis-à-vis the nascent Korean civil society during the USAMGIK period led those apparatuses to intervene with and control newly introduced institutions increasingly, thus inhibiting or refracting their natural growth.

In other words, the radical institutional grafting attempted by the USAMGIK failed to yield the intended effects due to the persistent influence of existing administrative institutions. For example, while the USAMGIK did introduce innovative labor policies that advocated the rights of workers, such policies nevertheless culminated in a growing repression of labor movements and left-wing politics. The tradition of the Korean government’s refusal to accommodate the needs of labor unions was set in stone during the USAMGIK period and persisted until the 1990s, when democracy finally began to take root in Korea. Similarly, the features of the free market system introduced in Korea by the USAMGIK remained nominal until the 1980s or so, as the Korean state continued to interfere with the market actively and frequently. These are only some of the patterns that originated in the discrepancy and tension between the old and new institutions that coexisted under the USAMGIK. The dynamics and contradictions among these different institutions served as significant restraints on the development and evolution of new and better institutions.

The institutions of politics, administration, capitalism, and democracy that the USAMGIK introduced in Korea have gone on to decide and shape Korean society at large and the evolution of public administration in general. The USAMGIK period, in other words, set the mold for later developments in Korean society, and as such is a highly significant period in historical terms. The USAMGIK’s failure to understand the unique history of Korea and the political, economic, and ideological conflicts rising in the nation undoubtedly shaped the institutions the USAMGIK introduced or maintained during its reign. The USAMGIK is criticized today for having initiated and strengthened the repressive use of state apparatuses, centralization, and state intervention in civil society that would later become internalized as norms. It is also blamed for enabling former collaborators of the Japanese colonial regime to rise to power and solidify their positions as the ruling elite in Korea for decades. Nevertheless, the USAMGIK deserves some credit for helping Korea overcome the dire economic crisis it was in, for establishing a market system (however limited at first), and for introducing Western-style democracy in the country.

Source: Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2008. Korean Public Administration, 1948-2008, Edited by Korea Institute of Public Administration. Pajubookcity: Bobmunsa.