Between Loyalty to the United States and Diversification of Allies: 1970s to the Mid-1990s

The détente and the eventual end of the Cold War caused a groundbreaking shift to the main pillar of Korean foreign policy that had been singularly centered on an active and tight alliance with the United States since the end of World War II. While Seoul still prioritized maintaining and securing Washington’s commitment to Korea’s security, it also sought to diversify the range of its allies and the scope of its foreign policy to counter anticipated changes in Washington’s pledge of commitment. The Korean government also sought to enhance the nation’s self-defense capacity based on rapid economic development. The complex interplay between loyalty to the American hegemony, on the one hand, and attempts to diversify and broaden the scope of Korea’s foreign relations and partnerships, on the other, first emerged during the last years of the Cold War and continued well into the years that followed.

(1) Domestic and International Conditions

President Richard Nixon’s so-called “Guam Announcement,” made on July 25, 1969, expressly acknowledged the limits of partnering with the United States as a main security strategy. Nixon exhorted the allies of the United States to bear responsibility for their own security, clearly indicating that Washington would no longer intervene with the survival and security of its allies so single-handedly. Although the Guam Announcement included a renewed promise to make good on Washington’s pledge of security for its Asian allies, it also represented a dilution of the strength of that commitment. In his address to the public on November 3, 1969, Nixon further clarified that Washington’s pledge of security for its allies would include providing a nuclear umbrella in which the United States had vital interests, and providing grants and aid for allies under attack.[1] The changing terms of Washington’s security pledge, however, sent reverberating shockwaves throughout Korea, a country that had so unquestioningly relied on the United States for protection.

The Nixon administration, furthermore, sought to withdraw all U.S. troops from Korea. Fearing that the worsening state of animosity over the Korean peninsula in the late 1960s might culminate into another Vietnam War-like situation, the Nixon administration promised to China, in the U.S.-China talks, to withdraw American troops from Korean soil and to enlist China’s cooperation in managing the state of affairs in East Asia (Jeon, 2005, 44-51; Cho, 2005, 65-67). Accordingly, the number of U.S. troops, which hovered around 61,000 prior to the Guam Announcement, declined to 54,000 by late 1970, to 43,000 by the end of 1971 (with the Seventh Division having backed out), and to 38,000 by the end of 1974. Although the Nixon administration insisted that these moves amounted to gradual reduction and not complete withdrawal, there is documented evidence that it was indeed the latter that Washington was actually angling for.[2] Although the changing tides of domestic politics in the United States prevented the materialization of complete withdrawal, the fear of it would haunt the Korean government ever after.

The Carter administration continued its predecessor’s policy of withdrawing U.S. troops from Korea, this time following a new foreign policy stance that sought to combine human rights concerns with security. Citing human rights violations and the suppression of democracy under the Yushin government in power in Korea at that time, the Carter administration announced its plan to withdraw American troops in 1977, and proceeded with the withdrawal in 1978. The summit of 1979 may have served to stem the escalating tension between the United States and Korea, occasioned by the withdrawal of U.S. troops, but was inadequate to dissolve Korea’s perception of increasing vulnerability to external threats in the absence of American troops (Park, 2007). President Carter’s plan to withdraw U.S. troops worldwide, however, ground to a halt in 1979 due to rising political objections in the United States and the deterioration of U.S.-USSR relations.[3]

Washington’s attempt to reduce the presence of American troops in Korea continued after the end of the Cold War as well. There was growing pressure inside Washington to roll back the United States’ military commitments overseas now that the rivalry with the Soviet Union was effectively over. In response, the Department of Defense (DoD) submitted the East Asia Strategy Initiative (EASI) to Congress in 1990. The EASI envisioned withdrawing all American troops from Korea over the subsequent decade, and immediately led to the withdrawal of 7,000 troops in 1992 alone. While the end result envisioned by the EASI never materialized due to the North Korea nuclear problem, the EASI confirmed that Washington could always backtrack its commitment to Korea’s security should political and strategic circumstances shift.

In the meantime, the astonishing growth of the Korean economy served to somewhat offset fears over the complete withdrawal of U.S. troops. The Korean economy was mired in a seemingly impossible postwar reconstruction process until the late 1950s, and began to grow at a dramatic pace in 1961. Figure 2-5 shows the miraculous growth in gross domestic product (GDP) Korea achieved until the mid-1980s or so. Korea entered the upper 30th percentile in terms of GDP distribution worldwide in 1966, the upper 20th percentile in 1970, and the upper 10th percentile in 1987. Korea’s GDP per capita maintained an equally impressive growth rate during the same period. Although Korea may have stepped down a few rungs on the scale of international GDP per capita distribution as resource-rich, newly independent nations began to develop in the late 1960s and early 1970s, it continued to make progress into the upper percentiles. Korea entered the upper 50th percentile in terms of GDP per capita for the first time in its history in 1976, and the upper 30th percentile in 1991 (Heston et al., 2006). The Korean economy, in other words, achieved dramatic growth in both the quantitative and qualitative sense.

Such speedy economic development provided the foundation upon which Korea could pursue and pave its own way of survival as an independent, self-sufficient nation. As shown in Figure 2-1, South Korean military spending began to exceed its Northern counterpart in 1976, particularly because the reduction in the number of U.S. troops led the South Korean government to introduce and levy the defense tax in 1975. This turnaround in military spending between the two Koreas grew wider and irreversible, as did the economic gap between the two countries. Seoul began to reinforce its conventional military power and contemplate development of nuclear weapons, launching activities to that end in late 1971 (Park, 1989; O, 1994; Meyer, 1984, 172). Having detected signs of nuclear weapons in development in South Korea in 1975, Washington sought to bring the program to an end by extending its nuclear umbrella (Min, 2004, 129-135; Mazarr, 1995, 27).

Source: Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2008. Korean Public Administration, 1948-2008, Edited by Korea Institute of Public Administration. Pajubookcity: Bobmunsa.

(2) Diversification

The increasing uncertainty accompanying dependence on Washington for national security led the Korean government to seek new signs of U.S. commitment to Korea’s security while also diversifying the range of its allies worldwide. While Korea stolidly remained within the hegemonic world order led by the United States, it also busily worked to enhance and expand its foreign relations with other countries with a view to mitigating the risks associated with over-dependency on the United States. This attempt was most evident in the patterns of resident envoys Korea sent and received during this period. Figure 2-2 shows explosive growth in the number of countries with which Korea established diplomatic channels in the 1970s. There are two noteworthy patterns here. The first is that Korea significantly improved its relations with nonaligned states. Seoul grew increasingly aware of the importance of maintaining good ties with these nonaligned states in the mid-1960s, when Pyongyang sought to strengthen its relations with those countries. As it became clear that Washington would no longer exert pressure on these nonaligned states on behalf of South Korea in the 1970s, Seoul felt compelled to establish and maintain ties with these states on its own. The North-South Korean rivalry thus extended into the realm of nonaligned states. The second is that South Korea sought to reinforce its relations with the West. While it would be impossible to find a new “patron” equal to the United States, Korea nonetheless pursued relations with Western states other than the United States and the United Kingdom. These attempts, in particular, culminated in growing efforts to increase imports from France, a Western state that had nonetheless remained relatively neutral.

Surprisingly, the Korean government also sought to improve ties with Communist states as well, beginning with the Declaration of June 23, 1973. President Park insisted on “opening up the Korean economy to all nations worldwide based on the principle of equal and mutual benefits,” and exhorted that the new initiative be extended even to regimes that did not share an ideology in common with South Korea. The declaration did not bear concrete fruit until the mid-1980s or so due to the lingering Cold War, but spoke to the breadth and depth of efforts made by the Korean foreign policy establishment to diversify the country’s foreign relations and partnerships.[1]

Once the Cold War came to an end, Seoul resumed its northward policy and successfully diversified its diplomatic relations and channels. The northward policy began with establishing relations with the states of the Eastern Bloc in 1989, and culminated in resuming diplomatic ties with Beijing in 1992 (Jeon, 2004, 26-30). It was during the heyday of this northward policy that the number of states to which Korea dispatched its resident envoys peaked, before dipping again at the policy’s conclusion. The success of the northward policy indicates South Korea’s victory in its rivalry against the North and also the dwindling level of influence collectively exercised by nonaligned states. South Korea took a more selective approach to sending resident envoys abroad, installing diplomatic establishments only in important locations. On the contrary, the number of states sending resident envoys to Korea continued to increase steadily, reflecting the growing economic and political importance of the country after its democratization.

The Korean government’s position on deploying its troops overseas for foreign wars during the 1990s reveals another interesting aspect of Korea’s diplomatic diversification policy. During the First Gulf War in 1991, Korea refrained from volunteering its troops, apparently out of sympathy for the plight of the affected Arab states. Instead, the Korean government sought to appease both the Arab World and the United States by deploying medical and airborne units to the former and simultaneously providing logistical and financial support for the latter. Even for peacekeeping operations helmed by the United States, Seoul deployed only minimal numbers of noncombat troops or military observer groups, indicating its growing wariness of proceeding unquestioningly with support for the United States (Lee, 2002, 305-319).

Source: Heston et al., 2006

[Figure 2-5] Korea’s Economic Growth

(3) Changes in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

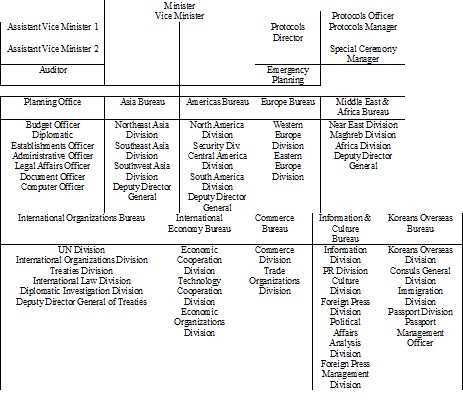

Korea’s simultaneous pursuit of diversification and consolidation in relation to its alliance with the United States was evident in the changing organizational structure of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as well. Under Presidential Decree No. 6456 of January 16, 1973, the Euro-America Bureau was broken up into the Americas Bureau and the Europe-Africa Bureau, reflecting the continuing centrality of the United States in Korean foreign policy as well as the growing importance of the emerging African states. Presidential Decree No. 7579 of March 18, 1975, further divided up the Europe-Africa Bureau into the Europe Bureau and the Africa-Middle East Bureau, and placed the Deputy Director General under the Director General of the Africa-Middle East Bureau. Presidential Decree No. 9326 of February 14, 1979, further broke up the Africa-Middle East Bureau into the Middle East Bureau and the Africa Bureau. The expanding organization of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the 1970s closely reflected a world order in transformation following the birth of newly independent states (MGA, 1987, 573-574).[2] While Figure 2-6 shows the merger of the Middle East and Africa bureaus, the growing importance of various regional bureaus in the ministry’s organization is also evident.

The structure of Korea’s diplomatic establishments abroad during this period was also reflective of the two-tracked Korean strategy. First, the concern with diversification is apparent in the increasing number of diplomatic establishments set up in such non-traditional regions as Asia, Africa, and Latin America. This pattern considerably diverges from the past practice, during the 1950s, of opening up such establishments in the United States, Western Europe, and only a few Asian states. Korean diplomatic offices began to crop up in Africa in the 1960s, and multiply in Europe and Latin America at the same time. The number of diplomatic establishments in the United States also grew rapidly. In addition to the main embassy in Washington, and the consulates general in Los Angeles, New York City, and San Francisco, the Korean government went on to open consulates general in Houston and Chicago on June 1, 1968, as well as in Seattle on August 27, 1977, in Boston on March 29, 1979, in Miami on March 29, 1979, and in Anchorage on May 22, 1980 (MGA, 1987, 628-633).[3]

Source: MGA, 1987, 620

[Figure 2-6] Organization of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs during the Economic Growth Period

(Announced on April 3, 1987)

Source: Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2008. Korean Public Administration, 1948-2008, Edited by Korea Institute of Public Administration. Pajubookcity: Bobmunsa.