official aid

Broad overview of US aid in Korea

Does aid have a positive impact on development? It is as much a moral question as it is an economic and political one. Any attempt to answer this question must be done in light of these three poles. Aid was critical in averting a humanitarian crisis in the wake of World War II and the Korean War in a poor country that had just been freed of its colonial rule. Foreign aid had a huge impact on Korea’s reconstruction and development; it raised to a large extent Korea’s capital stock primarily in human capital (education and health) and basic physical infrastructure (roads, railways, power, water, and sanitation); and it provided critical loans to finance industrialization.

But the great geopolitical uncertainty of the Korean Peninsula right after WWII, Korea’s eventual physical partition, which culminated with a civil war, never allowed development to get traction in the early years of the republic. By the late 1950s, signs of Korea’s economy increasingly becoming aid-dependent were emerging. A large part of foreign aid was comprised of commodities, which suppressed agriculture prices and distorted the incentives of farmers. Indeed, rice production decreased from 14.7 million Sok in 1949 to 12.8 million Sok in 1956, indicating 13.3% decrease (Lee, Dae-Keun, 2002). Besides the import of US grain flooding the Korean agricultural market, agricultural production decreased since around the time of land reform due to the small scale of farming land and weak agricultural institutions for credits and fertilizer. As a result, farmers’ income, which had increased after the land reform in the late 1940s and early 1950s, fell back. Such reduction of income led to a rapid expansion of farmers’ debt as they received loans from the informal credit markets. Because the Korean economy was driven by investments and consumption of aid commodities, funded by aid resources, it can be argued that a drop in US aid could result in a drop in GDP growth. Lee (2002, p354) shows that Korean GDP began a decreasing trend from a peak of 8.7% in 1957, when the amount of the US aid also peaked, to 2.1% in 1960.12 Moreover, the Korean government had become addicted to aid, overvaluing its currency to maximize aid receipts and printing money to meet budget needs. This made the economy susceptible to persistent high inflation and any attempt to keep macro stability difficult. Possibly more detrimental to the Korean economy, the over reliance on aid had given way to corruption and crony capitalism within government and business, itself becoming an obstacle to economic reform and progress.13 As the 1960’s began, Korea’s economy was by all intents and purposes dependent on aid while the failures of the Korean government gave merit to the label of a “basket case.”

In the 18 years after its liberation in 1945, following World War II, Korea suffered from a depressed economy, hyper-inflation, and a civil war, any one of which could impoverish a country. After the Japanese departed,14 Korea’s economy was left a shell of its former colonial self. Korea’s trade with Japan accounted for over 80% of total trade while Japanese technical workers accounted for 82% of the total technical workers .15 But Korea’s colonial past also meant that the remnants of Japanese technology and knowledge as well as public institutions, left it the building blocks from which to build from. Besides instituting a statutory basis and a structure of government administration, the Japanese built a network of railways to transport goods and natural resources, and to connect Korea with other Japanese territories

.15 Railway network was fairly robust stretching a total of 6,362 km (South Korea: 2,642km, North Korea: 3,720km) as of 1945. The less impressive Japanese built a network of roads across the Korean Peninsula, which was better in the South. Streetcars which ran on electricity were built in Seoul, Busan and Pyungyang. There were also harbors in Busan, Inchon, Kunsan and Mokpo which were largely used to facilitate trade with Japan. Korea was also able to produce a total of 988,700 KW of electric power, in which 92% of the power produced was located in North Korea.

[Table 1-1] The Share of Korean Technical Workers out of Total Technical Workers

|

|

Total number of technical workers (A) |

Korean technical Workers (B) |

B/A (%) |

|

Mining (As of 1941) |

|

|

|

|

Mining |

5,247 |

1,542 |

29.4 |

|

Smelting |

1,432 |

150 |

10.5 |

|

Sub total |

6,679 |

1,692 |

25.3 |

|

Manufacturing (As of 1944) |

|

|

|

|

Metal |

1,214 |

133 |

11.0 |

|

Chemical |

2,004 |

222 |

11.1 |

|

Civil engineering and Construction |

2,347 |

551 |

23.5 |

|

Miscellaneous |

2,911 |

726 |

24.9 |

|

Sub total |

8,476 |

1,632 |

19.3 |

|

Total |

15,155 |

3,324 |

21.9 |

[Table 1-2] Korea’s Natural Endowment and Economic Productive Capacity as of 1945

|

|

Unit |

Total |

South Korea |

North Korea |

|

Area of land |

Km |

220,796 |

93,634 |

127,136 |

|

Population |

Person |

25,917,881 |

17,891,699 |

8,026,182 |

|

Rice output |

1,000 Sok |

19,374 |

13,718 |

5,656 |

|

Area of forest |

Chongbo |

16,277,854 |

6,856,433 |

9,421,421 |

|

Manufacturing production |

1,000 won |

1,495,169 |

705,326 |

789,843 |

|

Anthracite (coal) Production |

% |

100 |

2.3 |

97.7 |

|

Annual Power production |

KW |

988,700 |

79,500 |

909,200 |

|

Railroad network |

Km |

6,362 |

2,642 |

3,720 |

|

Road network |

Km |

25,550 |

16,241 |

9,309 |

|

Harbor Handling Capacity |

1,000 ton |

18,000 |

10,000 |

8,000 |

12 Mason et. al (1980, p204) also concluded that aid was critical to driving Korea’s economic growth, citing the study by David Cole who estimated that aid contributed as much as 1.5% of GDP growth.

13 Much has been said about the exploits of President Syngman Rhee, who as an outsider was more interested in the politics than the economics of Korea, spending most of his energy and the country’s resources soliciting political influence. The government under President Rhee was known to be inept and corrupt resulting in much rent seeking behavior.

14 During the Japanese colonization, a total of 700,000 Japanese immigrated to Korea.

15 According to economic historian Dae-Keun Lee (2002), Korea’s manufacturing accounted for less than 5% of total production in early 1900s, but the share of production in manufacturing grew rapidly to over 40% by 1940 during Japanese colonization. By this time, Korea’s manufacturing sector experienced a fairly rapid transition from light manufacturing to heavy and chemical industries, much of it in the North. During the period 1931-1940, the share of HCI manufacturing increased

Source: Kim, Jun-Kyung and Kim, KS. 2012. Impact of foreign aid on Korea's development. Seoul: KDI School of Public Policy and Management.

The introduction of a modern education system also occurred during Japanese colonization though it was very limited to males and primary education. Indeed, as seen in , Korea had very high illiteracy rate, which was 77.7% in 1930, where the illiteracy rate for women was 92.0% and 63.9% for men.

|

decomposes the illiterate population by age groups. From the Table, it can be seen that high portion of the younger population was illiterate, which makes us conclude that access to primary education was very low. The illiteracy rate does not seem to have improved at all even at Korea’s liberation from Japan, which remained high at 78% in 1945 for adults. As such, access to primary education presumably also did not improve. Formal education even at the primary level was not accessible by the general population. First, most Koreans, which were tenant farmers that made little income, were not able to afford education costs. Moreover, the Japanese colonial government suppressed any informal educational activities such as programs sponsored by newspapers and local communities beginning in the mid 1930s and only worsened as Japanese faced eventual defeat in WWII.

[Table 1-3] Korea’s National Literacy Rate as of October 1, 1930

Source: Chosun Daily Newspaper, Dec. 22, 1934. Yoon Bok Nam (1990), Korea University Ph.D. Dissertation on Social History of Korean Literacy

[Table 1-4] Korea’s Literacy Rate by Age as of October 1, 1930

Source: Chosun Daily Newspaper, Dec. 22, 1934. Yoon Bok Nam (1990), Korea University Ph.D. Dissertation on Social History of Korean Literacy.

Korea’s industrial base was dominated by the Japanese, which supplied the capital, technology and managerial know-how while Koreans supplied the labor. After the Japanese departed, the economy once developed to exploit Korea and serve its imperial ruler was no longer viable. With a political and economic vacuum left in its wake, the newly liberated Korea soon descended into utter social chaos that soon precipitated a humanitarian crisis. Such was the context in which foreign aid first arrived in Korea.

In the wake of the World War II, Korea fell under the auspices of the US Army Military Government (USAMG) by virtue of having been a Japanese colony. Emergency humanitarian relief and assistance was deployed under the Government Appropriations for Reliefs in Occupied Areas (GARIOA),16 which had three basic objectives: preventing widespread starvation and disease; boosting agricultural output; and overcoming a shortage in most types of commodities or consumer goods. The emergency assistance provided much needed humanitarian relief, staving off widespread starvation, disease, and social unrest through the provision of basic necessities, including food stuffs and agricultural supplies, which accounted for 35% and 24% of a total assistance, respectively, as seen below. Indeed, the provision of grain totaled 44% of the total grain supply in Korea by 1947, while the large amount of fertilizer imported to Korea led to the huge increases in agricultural production.

[Table 1-5] Commodity Composition of GARIOA Imports: 1945-49 (Unit: US$1,000, %)

Notes:

1) “Reconstruction” includes the following categories: automotive, building materials, chemicals, and dye stuffs, communications, educational support, fishing industry supplies, highway construction equipment, mining industry, office supplies, power and light, and railroad.

2) 1949 categories of aid goods, when differently classified, were allocated as follows: fertilizer is the only item in agricultural supplies; in “unprocessed materials” are raw cotton, spinning raw materials, crossties, bamboo, lumber and raw materials and semi-finished products; “reconstruction” includes chemicals, hides and skins, pulp and paper, cement; salt, iron and steel, machines and equipment, motor vehicle equipment, transport equipment, and rubber products.

Source: Mason et al. (1980. p170). Bank of Korea, Economic Review, 1955, p314 for 1945-1948; and Monthly Statistical Review, February 1952 for 1949. The categories listed for 1949 do not correspond precisely to those for 1948. Their allocation in the 1945-48 classification is indicated in Note 2).

US assistance was administered under the following objectives: establishing a free and independent Korea as pledged in the Cairo and Potsdam conferences, fostering a self-reliant country as a stabilizing force in Asia, and founding a new republic as an outpost of democracy (Mason et. al, 1980). But the objectives were shrouded in a cloud of great uncertainty, as Korea remained a physically divided country until late 1947. As such, longer-term reconstruction efforts were put off, which were assessed to be undesirable, too risky at the time, in light of the geopolitical uncertainty that arrested Korea. As Mason et al. (1980) write: “…the US Congress was reluctant to provide funding; the Korean question was still being debated in the UN; and the belief was held by many Americans that, because Korea would eventually be reunited, America had no real stake in a costly and taxing program aimed at economic development of a South Korea that might shortly be reunited with its northern half.”

As such, US assistance during 1945 to 1951 focused on short-term assistance to address immediate humanitarian relief by supplying basic commodities and supplies while only a small amount was used for reconstruction efforts. There were efforts in implementing a longer term and more sustainable economic development strategy under the Economic Cooperative Administration (ECA), but in reality, the ECA essentially operated like GARIOA, focusing on the import of commodities.

In 1948, the policy objectives of the US aid program were formalized under the ROK-US Agreement on Aid, shortly after the founding of the Republic of Korea (ROK) led by the new Syngman Rhee government. No sooner had Korea been cast free of Japan’s colonial rule than did the US impose a strict set of provisions and controls to insure that the aid funds were allocated and used efficiently, and not misused or misappropriated. Outlined under 12 articles of the ROK-US Agreement on Aid, it provisioned that the Korean government agree to stabilize prices, to privatize the proprieties formerly owned by the Japanese, and to liberalize markets, i.e. fair foreign exchange rate. The last provision on exchange rates was a cause of “often acrimonious donor-recipient conflict over stabilization policy” that would test the limits of the donor-recipient relationship (Mason et al 1980). The Rhee government was intent on maximizing foreign aid receipts by keeping an overvalued currency against the dollar.

The agreement also stipulated that the two governments had to implement mutually agreed upon fiscal measures aimed at balancing the budget, reducing fiscal expenditures, and maintaining a conservative money and credit supply. A consensus had to be reached on any subsequent changes to fiscal, monetary, and balance of payment policies as well as on a national reconstruction plan. Under Article 5, a counterpart fund account had to be established at the central bank where the proceeds of US goods provisioned under the assistance program and sold in the market place were to be deposited. The allocation and uses of the counterpart funds had to be mutually agreed by both governments. The conditional nature of the ROK-US Agreement on Aid was judged to be unfavorable and intrusive by the Korean government. In effect, it was a show of a lack of confidence on the part of the donor, which from the donor’s standpoint seemed justified in light of the recipient country’s failures in managing the economy and a poor governance track record. Mason et al. (1980) describes the Korea-US relationship:

“There were periods when Korean and American officials had similar and compatible views as to the objectives and appropriate forms of US assistance. There were other times when the disagreements were profound and often exposed to public view. Then, there were some critical turning points when a change in the substance, or form, or even the perception of the assistance precipitated a convergence or divergence of views and actions of the two governments which, in turn, had significant implications for Korean development and US-Korean relations.”

As a result, the assistance program suffered from policy inconsistencies and lack of support from the Korean government at the outset while the US believed Korea was slow to institute the stabilization policies and sought to maximize inflow of aid by maintaining an overvalued foreign exchange rate.17 Ultimately, the US held all the levers of aid, and ended up getting policy cooperation from the Korean government. It should be noted that the macro stabilization and fiscal austerity measures had real positive effects in checking hyperinflation and shoring up Korea’s fiscal budget, as well as laying the ground works for development. After liberation and the Korean War, the economy suffered hyperinflation caused by rapid expansion of the money supply as the government kept printing money to meet budgetary needs and finance the war.

[Figure 1-6] Consumer Price Inflation Rate

16 The GARIOA programs implemented in other occupied territories of the US were generally the same, since its main objective was humanitarian assistance. 17 The issue of setting up a “reasonable” exchange rate became a highly controversial issue, which was begrudgingly resolved by a “series of unsatisfactory comprises.” The US accused the Korean government of trying to maximize foreign exchange receipts by keeping an overvalued Won while the US government sought to minimize the allocation of dollars into the hands of Korean government officials.

Source: Kim, Jun-Kyung and Kim, KS. 2012. Impact of foreign aid on Korea's development. Seoul: KDI School of Public Policy and Management. By mid 1949, the Korean and US governments began preparations on economic reconstruction. The Korean government took the initiative by devising a five year reconstruction plan, centered on industrial development to promote the manufacturing sector. The Korean plan was considered to be too ambitious by the ECA; ultimately, unrealistic by the US Congress. In any case, the ECA reduced the size and scope of the original plan and submitted a three year reconstruction plan totaling US$350 million to the US Congress for approval. To make Korea a viable and self-sustainable country, the proposed plan as described by Mason et al. (1980) focused on three basic areas of capital investment: “development of coal, expansion of thermal power generating facilities, and construction of fertilizer plants, in that priority order.”18 The Korean recovery plan assumed that US assistance would end by 1953, and any balance-of-payment deficits would be met by private foreign investment and borrowings. However, the plan was strongly opposed by the US Congress and failed to be approved by one vote. The bill, HR 5330, was eventually revised and passed to a one year US$110 million development plan.19 As a result, the ECA had to pare down the size of the aid program especially in capital investments and to shorten the program’s duration.

These efforts would be for nothing, as war broke out on the Korean Peninsula with the invasion of North Korea on June 25, 1950, essentially grinding the aid and reconstruction efforts to an immediate halt, and reallocating resources for military and humanitarian assistance. Indeed, the order of priority had once again focused on humanitarian assistance first and development later. Under the UN flag, Korea received multi-lateral assistance of US$457 million, of which all but a fraction came from the US, as part of war time relief efforts. A military-administered relief and assistance program was organized under the UN and the civil relief program. Most notably, the Civil Relief in Korea (CRIK) was established. Much of the assistance was used for food stuffs, and textiles and clothing, representing 40% and 24% of total assistance, respectively. The UN relief efforts were crucial in preventing widespread starvation and disease.

[Table 1-7] UN Civil Relief Efforts (Unit: US $million, %)

Source: Lee (2002), The Korean Economy in the Post-Liberation period and the 1950s

Based on the premise that the Korean War would end fairly quickly and the Korean peninsula would once again be re-unified, the Korea Reconstruction Agency (UNKRA) was established in December 1950 to resume economic reconstruction efforts. In this sense, UNKRA’s mission was different from CRIK; in that, its goal was to “lay the economic foundations for the political unification and independence of the country (Mason et. Al 1980).” However, the war as it would turn out dragged on for far much longer than anyone anticipated. As a result, UNKRA’s role in its first and second years of establishment was limited. It was not until after the Korean War had ended that UNKRA was able to provide significant amount of assistance and support in the reconstruction of Korea’s economy: repairing devastated properties, providing rehabilitation supplies, transport, and services for Korean industry.

The funding source for UNKRA was largely provided by the US after efforts to mobilize a multi-national aid package based on voluntary subscriptions from 40 nations (35 UN member nations and 5 non-member nations) failed to materialize amid of great uncertainties surrounding the unification of Korea. Initially, the US had pledged to provide up to 66% of the total aid, however, the aid provided to Korea became bilateral between the US and Korea. About 40 countries pre-committed to provide a total of $208 million for funding UNKRA, however, only $122 million was mobilized and used for Korea’s rehabilitation (See Table 3-7). One salient feature of UNKRA aid was that the composition of the aid went toward economic productive capacity at 70% while consumption was 30%. This ratio was different from the aid efforts under GARIOA and International Cooperation Administration (ICA). Since UNKRA aid sought to facilitate reconstruction, aid was used to import equipment and to construct new factories including Inchon Plate Glass Factory, Moon-Kyung Cement Factory, and Sam-Duck Paper. UNKRA aid was also used to rehabilitate damaged industries such as Janghang Smelting Factory, large-scale textile factories, and coal mine. Some of the UNKRA aid was used to fund policy loans to SMEs in manufacturing and mining industries through the BOK which made loans based on recommendations of Ministry of Commerce and Industry (Lee, 2002).

[Table 1-8] UNKRA Supplies Received by Commodities, 1951-59 (Unit: US$1,000)

Source: Lee (2002, p323-324)

18 This plan was similar to a recovery plan implemented in Japan to increase production by investing in coal production used to increase power generation, which was used to produce fertilizer, and so on. 19 In the context of history, the opposition of the plan by the US Congress, as some have observed, may have had far reaching consequences beyond the plan’s suitability; in that, the actions of the US Congress could have been construed as symbolic of wavering US support of South Korea, and thus, a precursor to the North Korean invasion, as opposed to the widely cited speech by Dean Acheson at the National Press Club a few days later.

Source: Kim, Jun-Kyung and Kim, KS. 2012. Impact of foreign aid on Korea's development. Seoul: KDI School of Public Policy and Management.

After the ceasefire in 1953, the Korean peninsula was left war-torn, divided and in utter destruction. South Korea suffered massive social and economic damage; civilian causalities totaled nearly 1.5 million while the destruction of properties were estimated to be about US$3.1 billion, leaving nearly 43% of residential homes and 42-43% of industrial facilities damaged compared to pre-war levels. To help with reconstruction efforts, Korea received massive amounts of US economic aid totaling about US$3 billion. Moreover, military assistance as a share of total US bilateral aid began to increase after the Korean War, when military assistance comprised more than half of total US aid to Korea in the 1960s as seen below.20

[Table 1-9] US Assistance to South Korea: 1946-76 (Unit: US $Million)

Sources: Mason, Kim, Perkins, Kim and Cole (1989), p182

After the tragedies of the Korean War led to a false-start on Korea’s economic recovery plans, preparation for a national reconstruction plan resumed once more. Just as before the war, the Korean and US government found themselves in disagreement over Korea’s development strategy and the allocation and uses of aid resources. Again, economic historian Lee (2002) writes, the Korean government was intent on pursuing a development strategy oriented on capital investment to increase production. It, thus, proposed to allocate 70% of total aid to repair damaged industrial plants, leaving the rest to be used for consumer goods. The US aid administrators insisted on pursuing stabilization first, then development, placing priority on reining in hyperinflation caused by the expansion of debt to finance the war, and on securing a bare subsistence level of living. The imperative was securing macroeconomic stability and a self-sustainable path to development to reduce Korea’s dependence on foreign aid. In principle, the Korean and US governments knew where they wanted to go; they just didn’t agree on how to get there. It was clear to the US that the Korean government sought not only to secure as much aid as possible but also to allocate as much of the aid as possible to increase investment. In the end, the Korean government capitulated to US demands. Foreign aid was focused on increasing the supply of consumer goods and intermediate goods to curb inflation while providing basic essentials (Krueger, 1979).

[Table 1-9] Aids from US and UN by Types (Unit: $Million, %)

Source: Lee (2002).

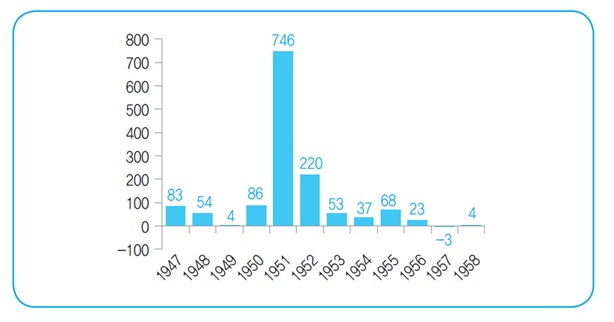

After the Korean War, the Foreign Operation Administration (FOA) was created in August 1953 to administer US aid with the objective of economic rehabilitation and military assistance. Between August 1953 and June 1955, the US provided a total of US$ 206 million in assistance to Korea, where 34% of the assistance went to facility investments, and 66% to consumption goods and raw materials .21 In June 1955, the FOA was renamed the International Cooperation Administration (ICA), while its main objectives remained unchanged. Under the ICA, a total of about US$ 1.3 billion of aid was disbursed, essentially the single largest aid program in Korea, peaking in 1957.

[Table 1-10] FOA Aid (August 1953-June 1955) (Unit: $1,000)

Source: Lee (2002).

20 After 1965, US aid was provided in the form of concessionary loans, and larger portion of US aid comprised of military assistance relative to economic assistance through the 1970s. 21 The planning and implementation of the reconstruction plan was conducted by the Combined Economic Board (CEB), a board comprised of representatives from the Korean and US government under the Agreement between the ROK and the Unified Command Concerning Economic Coordination signed in May 1952. The CEB convened on a regular basis to deliberate on important policy matters related to the allocation of aid funds and economic policy issues.

Source: Kim, Jun-Kyung and Kim, KS. 2012. Impact of foreign aid on Korea's development. Seoul: KDI School of Public Policy and Management. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||